Hypochondria is a Major Headache for Health Care and Insurers

Hypochondria is a Major Headache for Health Care and Insurers

The problem:

- Hypochondria has a lifetime prevalence of around 5.7% and is increasing in many countries

- It leads to substantially increased healthcare utilization and costs due to frequent doctor visits, unnecessary tests, medications, etc.

- Annual per capita costs of hypochondria range from $857 to over $21,000 based on studies from the US, UK, Denmark and Sweden

- The total economic burden is likely underestimated as most studies only looked at direct costs, not indirect costs from lost productivity, absenteeism, etc.

Causes of growth:

- Increasing general stress and anxiety levels in the population

- Wider access to medical information online leading to self-diagnosis and health fears

- More health-related media coverage and advertising increasing illness anxiety

- The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health anxiety

What can be done:

- Increase awareness and screening for hypochondria among healthcare providers

- Provide empathy and reassurance to hypochondriacs while avoiding unnecessary tests

- Refer hypochondriacs to cognitive behavioral therapy and medications proven to help

- Create standard diagnostic criteria and billing codes to better track hypochondria

- Collect more comprehensive cost data including indirect costs

- Increase access to preventive scans and self-monitoring tools to reassure the anxious

- Educate the public to counteract misleading online health information

- Reduce or eliminate direct to consumer advertising for medication

- Make medical information available online more clearly understandable, with quantification of risks and diagnosis frequency.

Is Hypochondria on the Rise in the United States?

For people that experience health anxiety, Google can be a tricky place. In the age of WebMD, searching for our symptoms can sometimes bring more questions than answers. Pair this with the first international pandemic since the Spanish Flu, and it’s quite possible that hypochondria is increasing in Americans.

We here at CertaPet wanted to know more about health anxiety in America, so we surveyed people across the U.S. to get some hard evidence. What percentage of the population consider themselves to be a hypochondriac? How often are they “self-diagnosing” themselves, or even their pets, via the internet? How has COVID affected health anxiety? We collected information about all of this and more.

Methodology

The survey we sent out asked people in the U.S. questions about their experiences with health anxiety, like how often they experience it (if at all) and if that amount has grown in recent years, what the leading causes of it are, how it has affected their behavior, and if they treat their illnesses differently than their pets’. The survey was done over a week in November 2021 and had over 800 total participants.

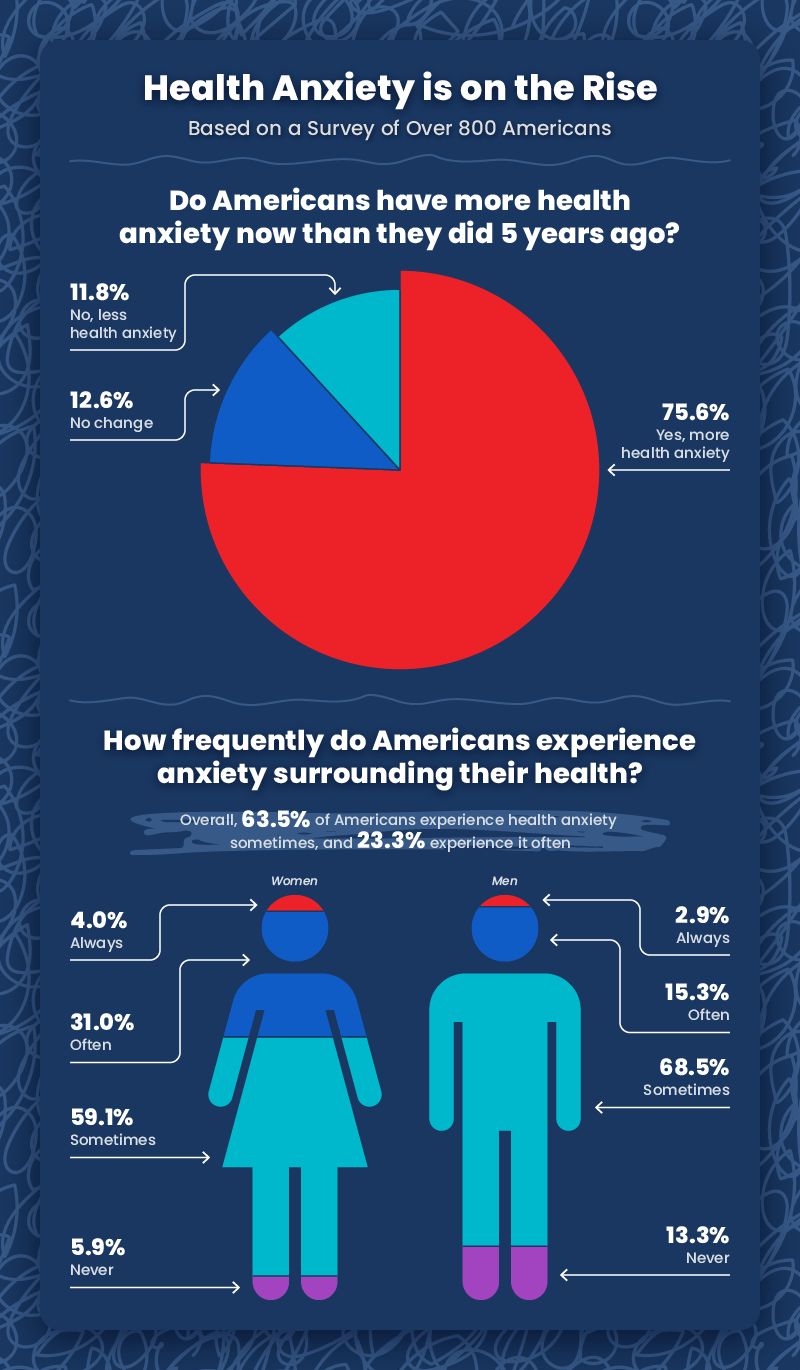

Health Anxiety is on the Rise

After looking at the data, it’s obvious that health anxiety among Americans is increasing, as 75.6% of Americans have more health anxiety now than they did five years ago. Regarding frequency, 63.5% say they experience health anxiety sometimes, 23.3% say they experience health anxiety often, and 3.45% say they experience health anxiety constantly. It’s safe to assume that some amount of all this health anxiety can be attributed to the pandemic, but it’s hard to give an exact percentage. We do have some pandemic-specific statistics that might give us a clue, but those are coming up a bit later.

There is an interesting gender takeaway to be found here as well. While men answered “sometimes” a bit more often than women, they also answered “never” over twice as much, while women answered “often” over twice as much in comparison to men. With 34.0% of women and 18.2% of men experiencing health anxiety at least “often,” it’s clear health anxiety plays a role in the lives of many Americans but women experience it more frequently, overall. Now let’s discuss why that might be the case.

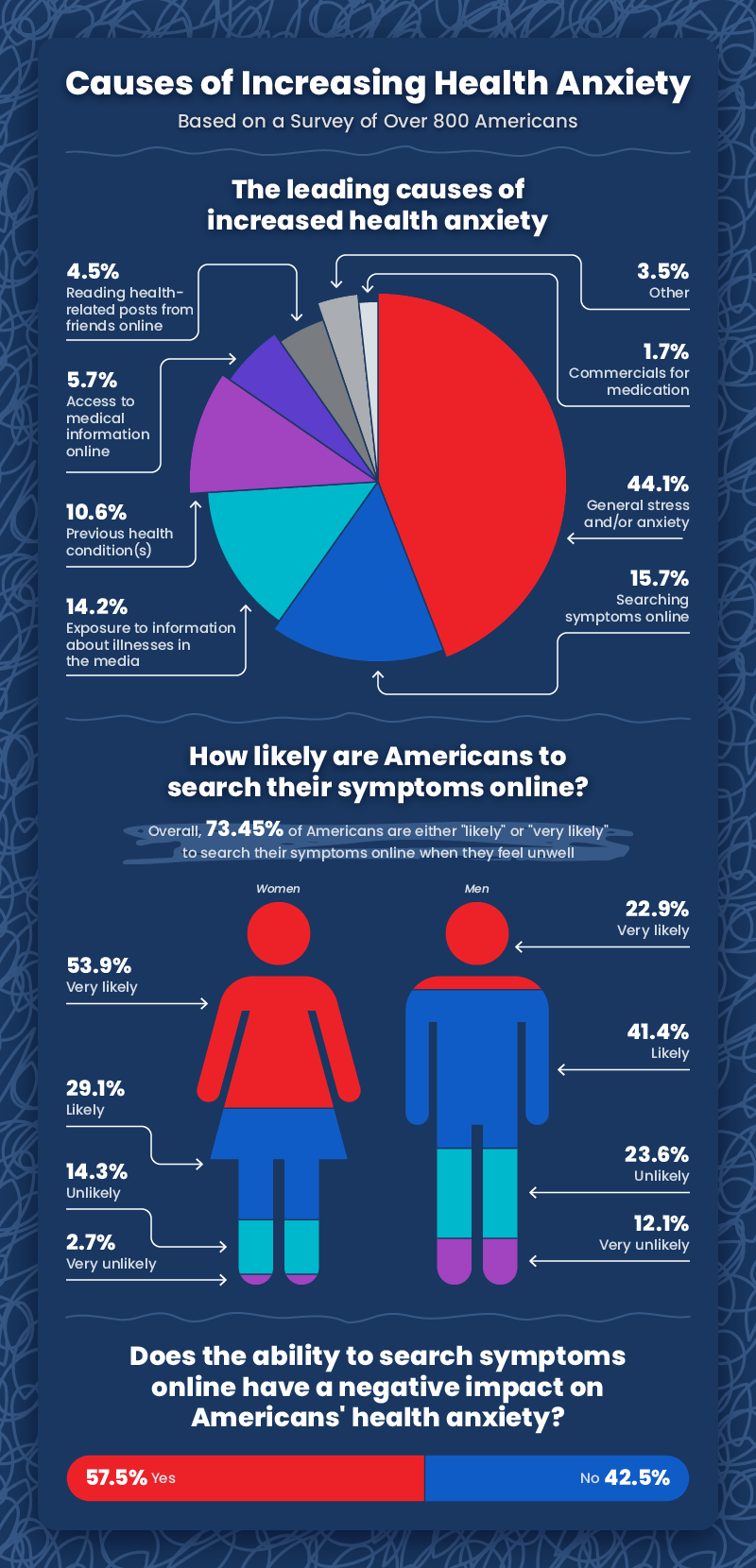

Leading Causes of Increasing Health Anxiety

So what’s the leading reason behind this increase in American health anxiety? With a 44.1% piece of the pie, our survey says it’s “general stress and/or anxiety.” That’s close to half of all responses. Now again, some of this large amount can certainly be pinned on the pandemic, but it’s hard to know exactly how much.

Let’s take a look at some of the other health anxiety explanations that survey takers chose. For 14.2% of respondents, “exposure to information about illnesses in the media” is the leading cause of health anxiety, which is something that can probably be blamed almost entirely on the astronomical jump in disease-centered media coverage that came with COVID, but the other two double-digit percentage options, the 15.7% of people who said “searching symptoms online” and 10.6% of people who said “previous health condition(s),” are a bit more complex.

For starters, searching up symptoms on the internet wasn’t possible 25 or more years ago, so this 15.7% number is evidence of an increase in the number of people that experience health anxiety since at least the invention of the Internet. The 10.6% that blame a previous health condition, however, can’t really be pinned to any particular time period. People have always gotten sick, and surely that’s occasionally instated present and/or future health anxiety.

The smaller percentages here don’t account for much, but other than the 1.7% “commercials for medication” and 3.5% “other” options, every remaining factor can be pooled in with our hypothesis that the Internet has played a role in increasing health anxiety across America (5.7% of respondents identified “access to medical information online” as a leading factor and 4.5% of respondents selected “reading health-related posts from friends online” as contributing to their health anxiety).

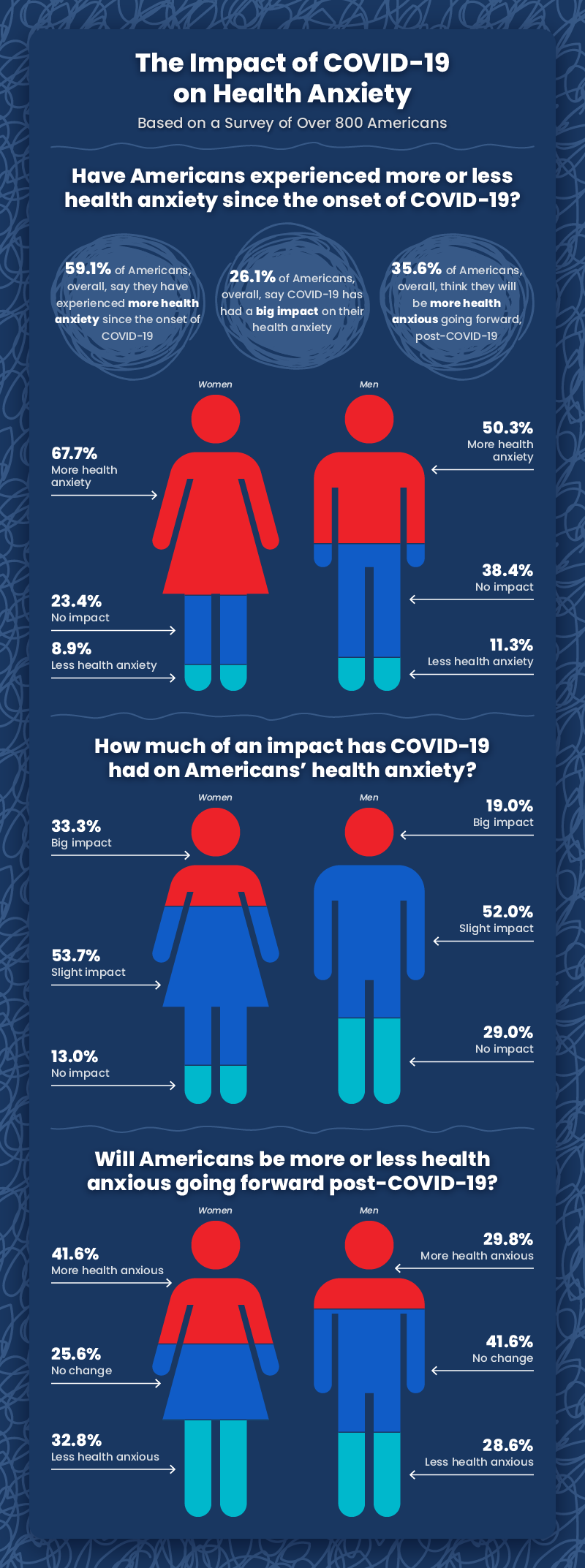

The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Anxiety

We’re finally at the pandemic-specific data, and it’s pretty much what we’ve been expecting. A whopping 59.1% of Americans say they’ve experienced more health anxiety since the beginning of the pandemic. If we look at women specifically, however, that number hits 67.7%, or just over two in every three American women. One in three American women even goes so far as to say COVID has had a “big” impact on their health anxiety.

Results are a bit mixed in the final row of charts, as both men and women are fairly split in how anxious they will be going forward post-COVID-19. This could be due to the uncertainty that the future inherently holds, or maybe some people think COVID potentially dying down will decrease health anxiety going forward while others believe the pandemic will have permanently changed perceptions of health by the time it’s finally over, if that time comes.

How Health Anxiety Impacts Our Behavior

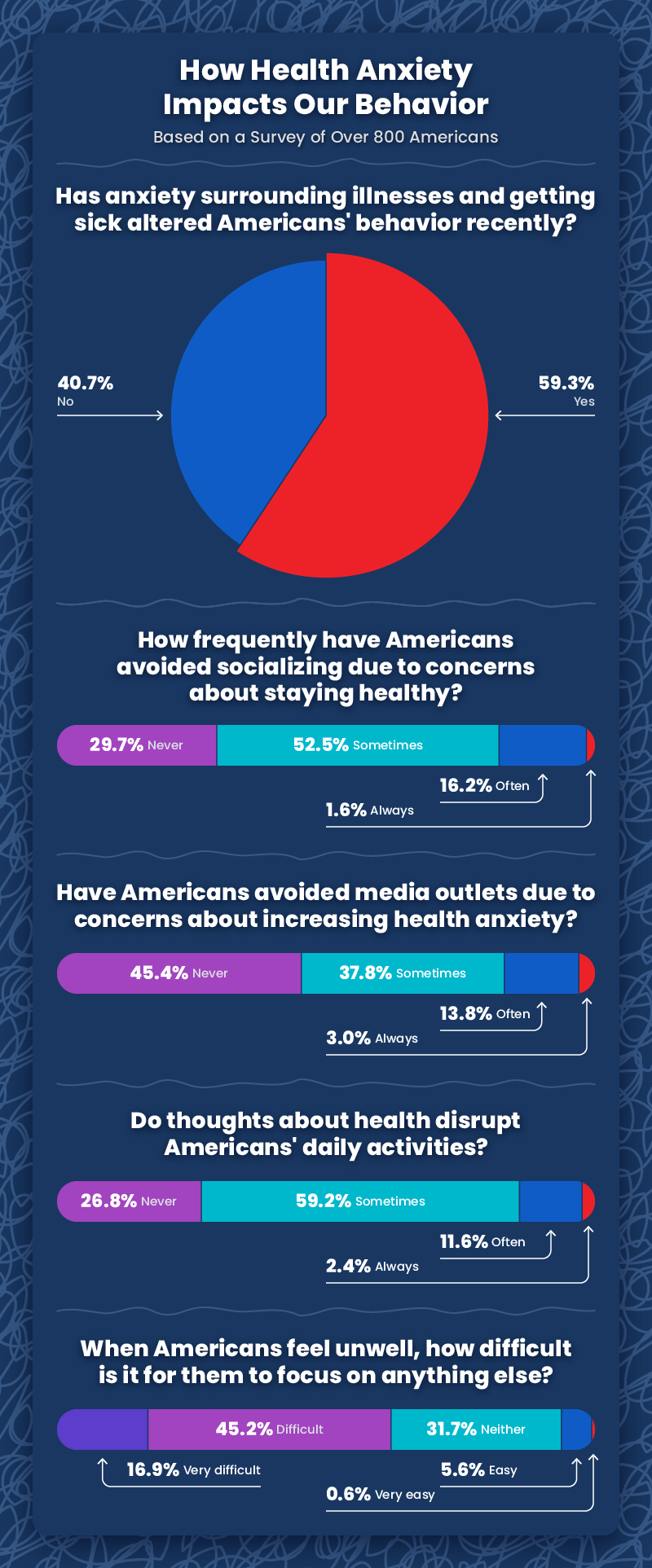

Americans aren’t just aimlessly worrying about their health either. While 59.1% say they’ve experienced more health anxiety since the start of the pandemic, 59.3% say that health anxiety has had an active effect on their decision-making. Specifically, 70.3% weigh health anxiety to some extent when deciding whether or not to socialize in-person while 54.6% take it into account when considering reading, watching, or listening to the news.

Health Anxiety and Our Pets

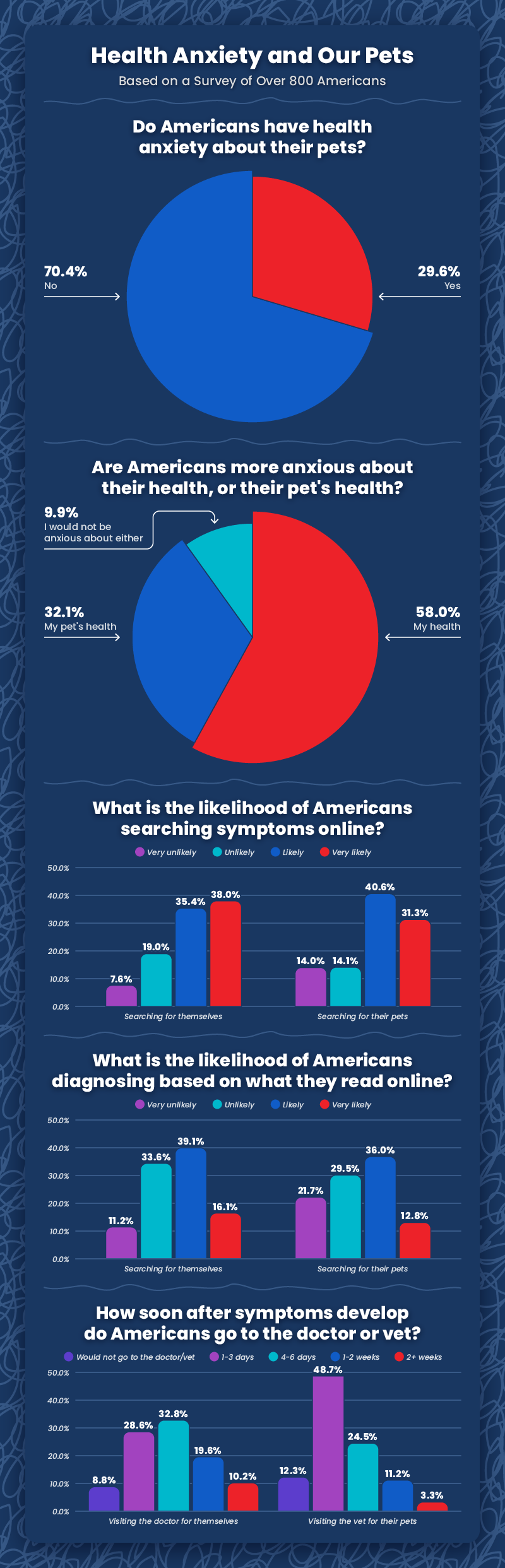

People aren’t just concerned with their own health, however. While a whopping 90.25% of Americans say they experience health anxiety at least occasionally, just under 30% of pet parents say they experience health anxiety regarding their pets. And of these pet parents, 58% say their own health gives them more anxiety, while 32.1% say their pets’ health gives them more anxiety. That means that, once people get a pet, there’s almost a one in three chance they start thinking about their pets’ health more often than even their own!

This idea is further supported by our next dataset, as, while only 37.4% of Americans will go to the doctor within the first three days of experiencing symptoms, the majority of respondents, 61%, will take their animal to the vet within the first three days of any symptoms appearing.

Closing Thoughts

To answer the question we posed in the title of this article, hypochondria is definitely around, as 9.62% of Americans self-identify as hypochondriacs, but the numbers tell us that the health anxiety that’s on the rise often comes in a less severe form. For example, while 11.6% of survey respondents said that health anxiety disrupts their daily thoughts often, and 2.4% said that disruption is a constant issue for them, 86% said they are only occasionally disrupted or never disrupted by thoughts of health anxiety.

It’s obvious that most pet parents care a lot about their animals. Some of the statistics that came up in this survey, like such a large percentage of respondents answering that their pets’ health often concerns them more than their own, is the kind of thing that we here at CertaPet can understand. Animals have such an incredible impact on our mental and emotional health, and many individuals turn to emotional support animals or psychiatric service dogs to help them cope with anxiety. If you think you might benefit from the support of an emotional support animal or psychiatric service dog, you can learn more about the process of getting a letter (a.k.a. prescription) for one on our website.

Dangers and Opportunities of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising

The average television viewer in the United States (US) watches as many as nine drug advertisements per day and about 16 hours per year, far exceeding the time an average individual spends with his/her primary care physician.1 Since 2012, spending on drug commercials has increased by 62%, and $5 billion were spent on drug commercials last year.2 Given their ubiquity, the article by Klara, et al. in this issue of JGIM offers one more piece of evidence to indicate that this medium is not operating as intended, and to force us to consider alternatives to the status quo.3

First, it is important to consider the history and original purpose of direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising. In the 1960s, Congress granted the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulating authority of prescription drug labeling and advertising. This authority included ensuring that ads (1) were not false or misleading, (2) presented a “fair balance” of both drug risks and benefits, (3) included facts that are “material” to a drug’s advertised uses, and (4) included a “brief summary” that notes every risk described in the drug’s labeling.1 While the first DTC advertisement was a Merck print advertisement for the Pneumovax® vaccine in 1981, DTC advertising exploded in the late 1990s after the FDA eased up on regulations for required risk information by stipulating that ads must include only the “major risks” and provide resources that consumers can be directed to for full risk information.1

As the regulating body of DTC advertising, the FDA is responsible for ensuring that advertising “is truthful, balanced, and accurately communicated” through regulation, surveillance, and education.4 In this capacity, the FDA has won substantial law suits and enforced penalties against pharmaceutical companies. For example, in 2012, Glaxo Smith Kline paid $3 billion and Abbott paid $1.6 billion in penalties for miscommunicating information in DTC advertising, while Eli Lilly paid $1.4 billion and Pfizer paid $2.3 billion in 2009.5

Proponents of DTC advertising report that drug ads can serve many important roles for consumers. First, they may empower and engage patients to participate in their own health care through informing patients about disease, treatment options, safety risks, and public health warnings.1, 6 Second, they may avert underuse of effective disease treatments, and potentially increase medication adherence.1, 6, 7 Finally, they may strengthen patients’ relationships with their physicians.1, 4 Surveys conducted by the FDA in 2004 found that most surveyed physicians felt that DTC advertising made their patients more aware of treatments and feel more engaged in their own health care. Moreover, 27% of consumers were prompted to make an appointment with their physician to discuss a condition they had not previously discussed due to DTC advertising.4

In contrast, critics have noted disproportionate risks and hazards related to DTC advertising. DTC ads have been shown to misinform patients by over-emphasizing treatment benefits, under-emphasizing treatment risks, and promoting drugs over healthy lifestyle choices.1, 6 DTC advertising may also lead to overutilization and inappropriate prescribing.6 In a study published in 2005 by Kravitz et al., standardized patients were randomly assigned to make brand name, general, and no drug requests for DTC-advertised antidepressants to 152 physicians. Patients who requested drugs received them significantly more often than those who did not, suggesting patient requests have a dramatic effect on physician prescribing.7 Furthermore, critics argue that DTC advertising can impose strains on the patient-physician relationship and limit already limited appointment time with patients.1, 6

Perhaps the most significant critique of DTC advertising is its effects on rising drug costs due to over-prescribing of both inappropriate and brand name drugs (especially when cheaper generics are available). According to the Department of Health and Human Services, prescription drug spending in the US was about $457 billion in 2015.8 Much of these costs are absorbed by the government since Medicare and Medicaid are the single largest payers for prescription drugs. As such, the existing regulatory environment influences federal and state budgets, insurance premiums, and patient out-of-pocket costs.

In the thoughtful study by Klara, et al., we see evidence of defects in the information provided by DTC advertising.3 The authors systematically assessed adherence of DTC advertisements to FDA guidelines for ads airing in the US between January 2015 and July 2016, with specific emphases on balanced presentation of risks and benefits, quality of data presented, and off-label promotion. The authors found that among 97 advertisements reviewed by authors, the quality of data presented was low—26% provided quantitative information for efficacy and benefit, 0% provided quantitative information on risks, and 13% promoted off-label use of medications (which is banned by the FDA). This study demonstrates that DTC-televised advertisements are not fulfilling their original intended purpose.

The optimal role for the FDA as the regulating body of DTC ads is also commonly questioned. Many researchers (including the study authors) suggest that FDA guidelines are not prescriptive enough in terms of the extent and format by which quantitative benefits and risks should be presented. For example, Klara, et al. found a minority of DTC ads provided quantitative information about treatment benefit, and no ads provided quantitative information about risks.3 One could argue that it is not surprising they lack this information since these ads are not explicitly required to so. Additionally, FDA enforcement of rules for DTC advertising has been weakened by increased bureaucratic procedures. An example has been the reduced number of warnings issued after the Department of Health and Human Services began requiring all regulatory warnings to be reviewed by the Office of Chief Counsel. This has also led to delays that have caused regulatory warnings to be sent long after advertising campaigns have ended.1 Compounding these problems, significant staff shortages have resulted in a minority of DTC broadcasts actually being reviewed by FDA staff.1

How can we optimize the benefits of DTC advertising in empowering and engaging patients while minimizing the attendant risks of poor-quality DTC advertising? One option supported by the American Medical Association is banning DTC advertising.9 It is notable that, outside of the US, DTC advertising is banned in all other countries except New Zealand. However, prior attempts at terminating DTC advertisements in the US have failed due to constitutional arguments that banning DTC advertisements would limit commercial freedom of speech.1 Others (including the authors of the accompanying article) propose boosting FDA resources to provide more prescriptive regulations on the content of information presented in DTC advertising and enforcement of such regulations. Another suggested solution is the use of an unbiased entity, either to review all DTC advertisements for regulation compliance or to actually develop and disseminate DTC information to consumers independent of pharmaceutical manufacturers. Some countries’ governments have served as this unbiased entity, primarily in countries where the prescription drug system is nationalized. For example, in an effort to increase generic drug use in Portugal, the government launched a television and print advertising campaign in the 2000s promoting the prescription of generic drugs through sharing effectiveness data and economic advantages with the public. Over the course of 7 years, generic drug prescribing increased by ~ 20%.10

DTC advertising is not satisfying its goals of providing accurate and balanced information to patients, and is most certainly leading to increased costs for the system and for patients. In our era of rising health care costs and questionable sustainability of entitlements, one would expect the government to be more invested in delivery of high-value information to patients and providers and should consider altering its role to ensure that DTC advertising better serves its purpose. Moreover, as is evident by the issues with DTC advertising raised by the authors, the current problems with DTC advertising have resulted from a combined drift from its intended purpose and regulatory and resource limitations. Although virtually all stakeholders (including patients, providers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and private and public payers) are differentially affected by DTC advertising, they share a common goal of maximizing the value of drugs by delivering the right drug to the right patient at the right time. There seems to be a unique opportunity for a collective group with diverse members from the health care ecosystem to work together to devise solutions that optimize the benefits and minimize the risks of DTC advertising.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Parekh and Shrank are employed by UPMC and do work for the UPMC Health Plan’s Center for Value-Based Pharmacy Initiatives.

References

1. Ventola CL. Direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising therapeutic or toxic? Pharm Ther. 2011;36(10):669–674. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Klara K, Kim J, Ross JS. Direct-to-Consumer Broadcast Advertisements for Pharmaceuticals: Off-label Promotion and Adherence to FDA Guidelines. JGIM 2018. 10.1007/s11606-017-4274-9 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

6. Stange KC. Time to ban direct-to-consumer prescription drug marketing. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(2):101–104. doi: 10.1370/afm.693. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD. Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(16):1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Simoens S. The Portuguese generic medicines market: A policy analysis. Pharm Pract. 2009;7(2):74–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The global economic burden of health anxiety/hypochondriasis- a systematic review

- Research

- Open access

- Published:

BMC Public Health volume 23, Article number: 2237 (2023)

Abstract

Background

Recent studies have shown a lifetime prevalence of 5.7% for health anxiety/hypochondriasis resulting in increased healthcare service utilisation and disability as consequences. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic review examining the global costs of hypochondriasis, encompassing both direct and indirect costs. Our objective was to synthesize the available evidence on the economic burden of health anxiety and hypochondriasis to identify research gaps and provide guidance and insights for policymakers and future research.

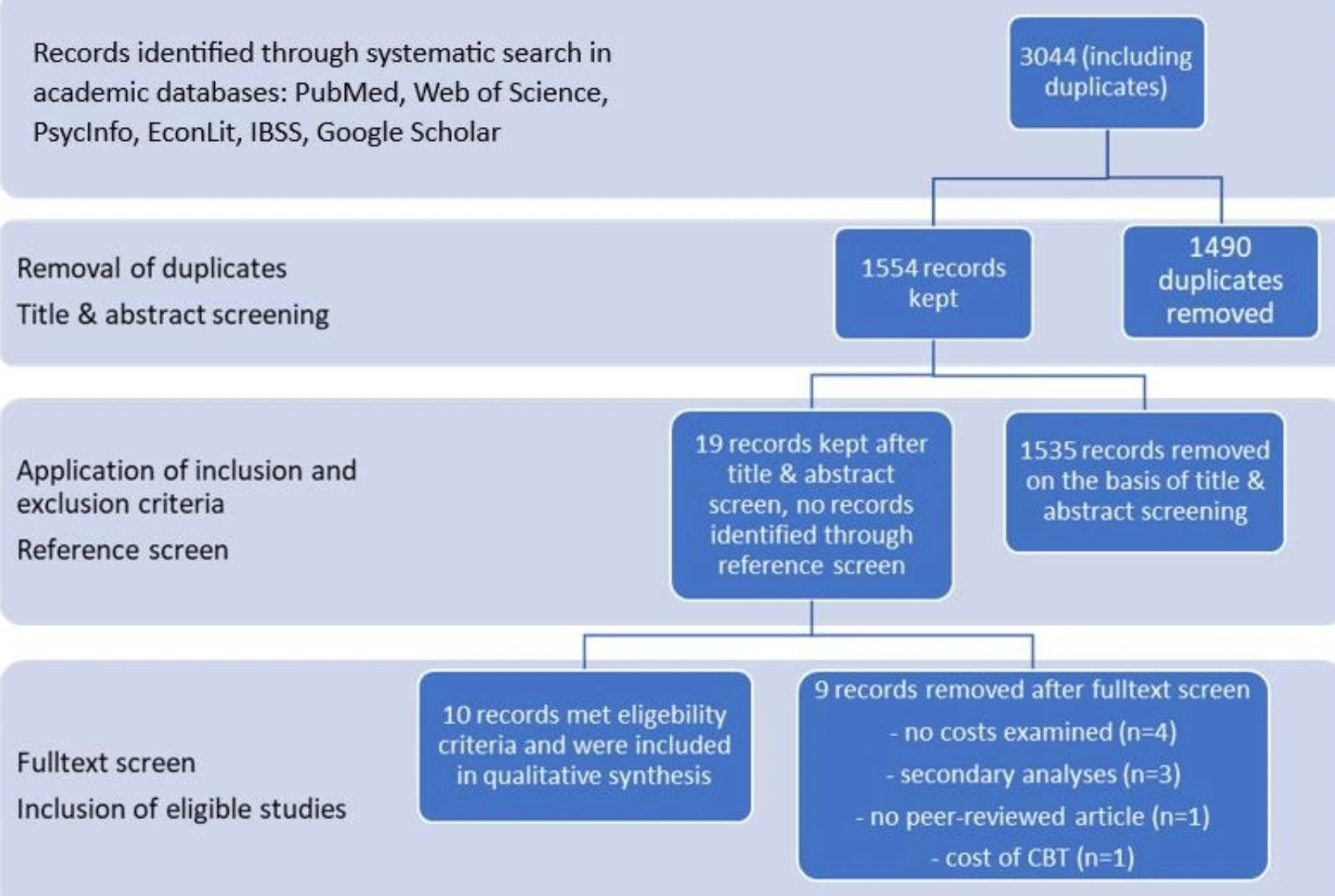

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Web of Science, PsycInfo, EconLit, IBSS and Google Scholar without any time limit, up until April 2022. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in this search and the following article selection process. The included studies were systematically analysed and summarized using a predefined data extraction sheet.

Results

Of the 3044 articles identified; 10 publications met our inclusion criteria. The results displayed significant variance in the overall costs listed among the studies. The reported economic burden of hypochondriasis ranged from 857.19 to 21137.55 US$ per capita per year. Most of the investigated costs were direct costs, whereas the assessment of indirect costs was strongly underrepresented.

Conclusion

This systematic review suggests that existing studies underestimate the costs of hypochondriasis due to missing information on indirect costs. Furthermore, there is no uniform data collection of the costs and definition of the disease, so that the few existing data are not comparable and difficult to evaluate. There is a need for standardised data collection and definition of hypochondriasis in future studies to identify major cost drivers as potential target point for interventions.

Introduction

Hypochondriasis or, sometimes also referred to as health anxiety, can be broadly defined as the pathological fear of suffering from a serious physical illness, poses a major economic burden on healthcare systems and society. One of the most recent studies on the prevalence of hypochondriasis in the general population was conducted in Australia, and found a lifetime prevalence of 5.7%, with a peak in middle age [1]. A systematic review on the prevalence of hypochondriasis by Weck et al. showed a range of 0.3–8.5% in a general medical setting (e.g., primary care) [2]. Data on the prevalence of hypochondriasis in children are scarce. In the Copenhagen Child Cohort Study, parents were asked about health anxiety symptoms in their children aged between 5 and 7 years. The study revealed that 17.6% of the cohort had symptoms, and 2.4% had significant symptoms [3]. The condition is associated with an increased use of health services due to regular doctor visits and elevated number of days on sick leave, compared to the general population, as patients suffering from hypochondriasis are convinced or afraid that they might have a serious illness [1, 4, 5].

There seems to be no uniform definition for health anxiety and hypochondriasis. In the literature, these two terms are often used interchangeably, but some authors define them as two separate entities. The DSM IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) categorizes hypochondriasis as a somatoform disorder involving the misinterpretation of physical sensations [5]. However, this definition has been criticized by several authors, who have called for reclassification. For example, Olantunji et al. argue that the focus of the disorder is on illness anxiety rather than somatic complaints [6]. In response to the criticism, hypochondriasis was replaced in the DSM V by two new diagnoses: somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder [7].

In terms of therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is considered the most effective treatment for the disease and can also be offered as an online therapy [8]. It is assumed that digitalization and almost unlimited access to information via the internet further fosters increases in the prevalence of health anxiety/hypochondriasis, which, in turn could lead to increased healthcare costs [9]. Excessive online searches for symptoms of illness are also referred to as cyberchondria [10].

Health costs can be categorized into different types. There are the tangible, monetarily measurable costs. They differ in the cost perspective, i.e., whether they are incurred by the service provider, the patient, or society. Tangible costs are further classified into direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are expenses directly related to the disease, such as transport costs, expenditures for specialized medication, home modifications due to a disease, or therapies that the patient has to pay for out of pocket. If therapy or prevention is covered by health insurance, these direct costs are incurred by the service providers. Administrative costs, personnel costs, expenses for doctor’s visits and diagnostics, or research are also considered direct costs. Indirect costs are reflected in productivity losses, increased absenteeism from work due to sick leave and the associated loss of wages. Another type of costs are intangible costs, which will not be discussed in detail here [11].

To the best of our knowledge, no existing systematic review has examined the economic impact of health anxiety and hypochondriasis on healthcare systems and societies at a global level. This paper aims to synthesize the available evidence on the economic burden of health anxiety and hypochondriasis, specifically focusing on total costs, including both direct costs of health anxiety/hypochondriasis caused by doctor visits, medication or administration and indirect costs resulting from absenteeism from work and productivity loss.

As the first systematic review in this field, a key objective is to emphasize the disease burden, enabling resource allocation, healthcare prioritization, and identifying research gaps to provide guidance and insights for policymakers and future research.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [12]. It is registered on the PROSPERO register for systematic reviews (registration number: CRD42021240018).

Search strategy

We started a preliminary search to detect relevant search terms and develop a search string consisting of (i) the disease hypochondriasis and related synonyms and (ii) search terms relating to economic burden. The latter included the terms „health anxiety“, „hypochondria*“, and „illness anxiety disorder“. The second part included the terms „cost*“ and „economic“. An asterisk has been added to the terms cost and hypochondria to include other terms with the same root word in the search. Search terms within a category were linked with the Boolean operator „OR“ and then enclosed with brackets, the categories themselves where then linked with „AND“.

We conducted the systematic literature search in the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, PsycInfo, EconLit, IBSS and Google Scholar. No restriction on publication year was applied. In Google Scholar, we screened the results for each search combination to saturation which means we continued screening until no more relevant articles appeared, and our subject area was adequately covered. After reaching saturation, 30 more articles were screened. Saturation was achieved within a range of 50 to 180 articles depending on the search term used. Later, we screened the reference lists of the included publications to detect further relevant articles. The search was conducted in April 2022.

Study selection

All database hits were imported into Rayyan to remove duplicates and to screen the records [13]. The title and abstract screening against eligibility criteria was carried out independently by HK and MK. The manuscripts whose title and abstract met the inclusion criteria underwent full-text screening. Disagreements and uncertainties were clarified by either bilateral consensus or discussion among all authors.

Eligibility criteria

We included any peer-reviewed study on the economic burden of hypochondriasis, such as direct costs, related doctor visits both primary and secondary care, medication, or administration as well as indirect costs resulting from absenteeism or productivity losses. Our systematic review included studies from low-, middle- and high-income countries. We encompassed all types of studies, including randomised controlled trials (RCT), quasi-experimental studies, observational studies, cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, and cost-of-illness.

We only included articles that reported costs incurred by health anxiety/hypochondriasis if the patients did not receive any special therapy like cognitive behavioural therapy. The rationale behind this criterion is that hypochondria still receives limited attention in diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, we aimed to showcase the costs that arise, particularly from untreated cases, to underscore the importance of adequate diagnosis and subsequent therapy for the disease. For comparative studies examining the cost of different forms of cognitive behavioural therapy, only the costs incurred by the control group, such as a waiting list control or treatment as usual (TAU), were included.

There was neither an age limitation of participants nor a date restriction regarding the publication date. Consequently, the included population consists of adults, young adults, and children. Included publications had to be indexed in English language.

Exclusion criteria

We did not consider studies that analysed the cost of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as well as internet-guided CBT (iCBT) as treatment for health anxiety. For better comparability and to examine the total costs objectively, we excluded studies that did not provide monetary values of incurred cost items, such as the frequency of doctor visits or number of days absent from work. Due to low quality of evidence, we did not include case reports, narrative reviews, expert opinions, or editorials.

Data extraction and cost conversion

The included studies were subjected to systematic analysis, and the relevant information was summarized in a predefined data extraction sheet. This data extraction sheet includes general information such as the title, author, journal, date of publication, country, study type, study objective, study setting, source of data, diagnostic assessment tool, definition of the disease used, and the time frame of the study. Additionally, the characteristics of the study participants, such as the number of participants, gender, and age, were analysed. Regarding our primary outcome, the total costs, as well as the different types of costs, were collected along with the corresponding currency. As reported costs related to different years, currencies and countries, all cost information was converted to US$ for the year 2022 using the CCEMG - EPPI-Centre Cost Converter [14].

Quality assessment

We assessed the quality of included studies using the reporting guidelines suggested by the equator network [15]. In the case of observational studies or RCTs, we used the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) and CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) checklists for the assessment. The basis of the evaluation was the number of fulfilled characteristics listed in the checklist. We scored one point if the criterion was completely fulfilled, half a point if it was partially fulfilled and no point if the item was not mentioned in the article. A reporting less than 70% was defined as low reporting quality, while 85% and above was classified as high quality. Everything in between was defined as medium quality. The quality assessment was also carried out independently by HK and MK. Disagreements were solved by discussion until consensus was reached. No studies were excluded due to poor reporting.

Results

Study selection

In total, our database search in 2022 yielded 3044 articles. After the duplicates were removed, 19 articles remained for full-text screening. The screening of references of included articles did not reveal any further studies.

Since three articles represented secondary analyses of already included studies, data of those studies were no longer considered. Four studies were excluded as there were no costs examined and one study was not peer-reviewed. Another study only looked at the costs of CBT without a control group. Finally, 10 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. (Fig. 1).

≥ST above or equal Somatization Threshold; <ST below Somatization Threshold; ≥ 18 older than or equal to; / not reported; STROBE The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology, CONSORT Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; HA Health anxiety; DSM-IV Hypochondriasis Diagnosis according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; CC Control Condition; SD Standard Deviation; CBT Cognitive Behaviour Therapy; RCBT Remotely delivered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy; ICBT Internet Based Cognitive Behaviour Therapy; iACT Internet-Delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; iFORUM Internet Forum; G-ICBT Therapist-Guided Internet Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; U-ICBT Unguided Internet Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; BIB-CBT Cognitive Behavioural Bibliotherapy; WLC Waiting List Control.

ST above or equal Somatization Threshold; DSM-IV Hypochondriasis Diagnosis according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; HA Health anxiety; GP General Practitioner; GBP Great Britain Pound; A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions; *outcome measure adjusted for patient’s sex, age group, type of insurance, and medical comorbidity

Results of general study characteristics

Geographically, the ten studies were conducted in four different countries (United States, Sweden, Great Britain/United Kingdom, Denmark), which all can be classified as high-income countries according to the World Bank income group classification [16]. Altogether they were covering only two regions: Europe and North America [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Two studies were non-interventional studies that compared the costs caused by hypochondriasis with the costs incurred by participants with other well-defined medical conditions [18, 19]. Six studies examined the cost-effectiveness of CBT, iCBT or internet delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy but included control groups that could be used to extract data for this systematic review [17, 20, 21, 24,25,26]. In four studies, the control groups received standard care. Participants assigned to standard care did not receive specific therapy but had the option to present to their general practitioner or clinic if needed. In two of these studies, it was explicitly mentioned that the patients were informed about the disease during the recruitment process, and in one study, their general practitioner was also informed about it [17, 21, 25, 26]. In two studies, the control group was given access to an online forum for peer interaction with other participants [20, 24].

While eight of the studies focused on adult participants suffering from health anxiety/hypochondriasis [17,18,19,20,21, 24,25,26], two studies examined health anxiety in children. These studies are part of the Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 and were conducted by the same research team [22, 23]. The more recent of the two studies was a follow-up study of the previous one [23].

All studies contained information on the sex distribution of the study participants, either in the form of percentages, absolute values, or both [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. One study did not provide information on the sex distribution with respect to the two study arms [25]. All studies were published between 2001 and 2022 [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Only six studies provided summarized information on the age distribution of study participants [17, 19,20,21, 24, 26] while Barsky et al. provided a frequency distribution for different age groups [18]. Since the data from the Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 were collected from the same participants in 2011–2012 and again in 2016–2017, the children were initially 11–12 and at follow-up 16–17 years old [22, 23]. The cost assessment conducted by Rask et al. referred to the 2 years prior to data collection [22].

For detailed information see Table 1. In terms of quality assessment using the STROBE and CONSORT checklist, 7 studies showed medium reporting quality [17, 19, 21,22,23, 25, 26], while three studies showed low quality of reporting [18, 20, 24].

Results of definition of hypochondriasis/health anxiety

Most of the included studies used the terms health anxiety and hypochondriasis interchangeably and employed similar assessment tools to identify the study participants [20, 21, 24,25,26]. Fink et al. replaced hypochondriasis with health anxiety due to stigmatization and introduced a classification system distinguishing between mild and severe health anxiety [19]. The aim of this new classification was to address the overlap of DSM-IV hypochondriasis with other somatoform disorders [19, 27].

The earliest study examined both hypochondriacal health anxiety and somatisation. The patients were given a questionnaire inquiring about somatic symptoms and hypochondriacal fears. Based on a predefined cut-off, the patients were classified as being above or below the somatisation threshold (see Table 1). Thus, an intersection of these two syndromes is examined here. Since at that time the scientific world made less of a distinction between hypochondriasis and somatisation disorders and, according to Barsky et al., all patients showed clinically relevant levels of hypochondriasis, we decided to include this publication nevertheless [18].

Only one study used the new DSM-V definition, which distinguishes between somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder. Both entities were accepted as eligibility criteria for recruitment [17]. In the children’s studies, the term health anxiety symptoms were used as there is still no clear definition of the disease in childhood [22, 23, 28].

Reported total costs and data source

Information extracted on the costs of hypochondriasis are shown in Table 2. Cost information was collected from administrative hospital databases (n = 1), hospital records (n = 1), questionnaires and official cost tariffs (n = 2) and national health registers (n = 6) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. While all studies reported direct medical costs related to outpatient care, these do not consistently represent identical cost components across studies, as can be seen in the “Type of Costs” column of Table 2. Additional direct medical and non-medical costs were reported by five studies [17, 19,20,21, 26], while three studies also estimated indirect costs related to hypochondriasis [17, 20, 24].

Total costs of hypochondriasis

In the USA, the total cost of hypochondriacal health anxiety and somatisation were 1964.91 US$ per patient for the 12 months preceding and 2089.21 US$ per patient for the 12 months following the index visit. As no information was provided on the financial reference year, we related the cost conversion to the year of data collection (1998) [18]. In Denmark, total costs ranged from 857.19 to 2956.62 US$ per patient per year, depending on the severity of the disease [19, 24]. Risor et al. have examined primary care, secondary care, and indirect costs in terms of productivity loss. The total primary care costs were 452.48 US$, the total secondary care costs were 701.70 US$ and the indirect costs were 1212.65 US$ [24]. Three studies conducted in the United Kingdom reported costs from 1294.95 to 7088.98 US$ per patient per year [21, 25, 26]. The two studies conducted in Sweden were the only ones to examine direct, indirect, and non-medical costs as well. These cost components were also included in the total costs from 15179.29 US$ to 21137.55 US$ per patient per year. According to Hedman et al. the total costs were made up of 4129.14 US$ for direct costs, 1369.27 US$ for non-medical costs and 9680.89 US$ for indirect costs. The indirect costs were therefore more than twice as high as the direct costs [20]. In the study of Axelsson et al. the total costs were made up of 8595.63 US$ for direct costs, 2089.21 US$ for non-medical costs and 10485.87 US$ for indirect costs [17]. The studies regarding the Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000 reflected total costs depending on symptom severity. These ranged between 120.52 and 353.09 US$ per year [22, 23].

Specific cost components

Five of the included studies examined the medication costs. To enhance comparability, these costs were also converted to annual costs in US$ for the year 2022. In Denmark, this resulted in costs of 400,13 US$ per year regarding DSM-IV diagnosis [19]. In Great Britain, one study showed costs of 2179.70 US$ and the second one 690.06 US$ [21, 26]. Sweden showed a large discrepancy with 39.12 US$ in one publication and 198.96 US$ annual costs in the other [17, 20].

As already mentioned, indirect costs were also examined in 3 publications. These are also made up of various cost components. In all studies, however, the cost item sick leave was examined. This resulted in annual costs of 419.67 US$ and 1432.60 US$ in Sweden and 1212.65 US$ in Denmark [17, 20, 24].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine the total costs of health anxiety/hypochondriasis. Our aim was to summarize the available evidence on the costs of hypochondriasis, especially when patients are not receiving treatment, in the form of CBT or other treatment approaches. We were able to identify research gaps and draw implications for future research and policy. This systematic review revealed a lack of data about indirect and direct costs of hypochondriasis. Research on this topic has only been conducted in the United States and 3 different countries across Europe. All of them are high income countries. There were large cost differences observed not only between but also within the countries investigated. The 12-month costs ranged from 857.19 to 21137.55 US$ [17,18,19,20,21, 24,25,26].

There are several factors that contribute to this heterogeneous data situation. Firstly, the studies did not use standardised definitions and classifications of health anxiety/ hypochondriasis. As previously mentioned the definition of this condition has been subject to major discussions in recent years [6]. In particular, the publication of the latest version of the DSM-V caused major changes, in which the term hypochondriasis was completely removed. However it is retained in the ICD-11 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) [7].

While some studies consider all participants above a certain cut-off point (e.g. short health anxiety inventory score ≥ 18) to be equally affected by health anxiety [18, 20, 21, 25, 26], other studies divide health anxiety into mild and severe. Accordingly, those studies present divided costs, which then turn out to be lower in comparison [19, 22, 23]. Studies that do not distinguish between mild and severe cases may have potentially captured inaccurately high or low costs. This is because we lack information on the number of participants with a severe manifestation, which consequently results in higher costs [17, 20, 21, 24,25,26]. Another study examined the costs of hypochondria and somatization; therefore, the costs are not directly comparable to the other outcomes as they may be over measured due to the overlap with the second disease component. Furthermore, the data were collected in 1998 and represent the sole existing data from the United States [18]. This highlights the scarcity of data and the subsequent lack of attention given to the condition in this region.

Additionally, different cost items were included in the studies and the type of data collection also influenced the type of cost detail.

This is a widespread issue in health economic studies. A systematic review conducted in 2021 compared various guidelines for health economic evaluations and revealed a substantial overall variability in determining which costs should be included [29].

While especially in Denmark national health registers were used [19, 21,22,23,24,25], the data of other studies were based on hospital databases [18, 26]. Data collection by means of health care registers has the advantage that data is directly available. This means that all costs in the area of primary care can be recorded, regardless of the institution [30]. In particular, the data collection from hospital data could underestimate the costs, as individuals with hypochondriasis tend to engage in “doctor shopping”, which refers to consulting different doctors for the same medical condition. Furthermore the doctor visits outside the hospital are not included in these studies [31].

For the control groups receiving standard care, the knowledge that the participants suffer from hypochondriasis may have influenced the costs. The information about the disease can be viewed as a form of mini-intervention, as the confrontation with one’s own illness may have a therapeutic effect. In such cases, the costs would be lower than expected.

Except for one study, all surveys were conducted in tax-funded health systems with no out-of-pocket payments. This could potentially impact resource utilization and, consequently, costs. However, it can also be inferred that the findings from these studies may not be generalizable to countries with different healthcare systems, particularly low- and middle-income countries.

A systematic review that examined the global economic costs of anxiety disorders has revealed that indirect costs account for a significant proportion of the total costs [32]. Since indirect costs were only investigated in three studies, it is not possible to make a reliable statement about the total costs of hypochondriasis. Although some publications suggest that overall costs are significantly higher when indirect costs are considered, research in this area is still lacking [17, 20, 24].

Health anxiety/ hypochondriasis in children

Research about hypochondriasis in children appears to be underrepresented. Only two studies, both conducted by the same team within the same cohort, attempted to gain further insights into the economic burden of the disease in this age group [22, 23].

One reason for the missing data could be that diagnostic criteria for hypochondriasis and somatoform disorders for children are still not established. This problem was already identified 25 years ago [28]. The Childhood Illness Attitude Scale was an attempt to identify “characteristics and dimensions of childhood health anxiety” to enable the development of diagnostic criteria for hypochondriasis in children [33]. Interestingly the economic burden resulting from hypochondriasis in children seems to be lower compared to adults. On the one hand, the classification into high and low levels of health anxiety contributes to this phenomenon. On the other hand children are less likely to utilize health services independently because they are dependent on their parents and need to persuade them of the necessity of visiting a doctor [28].

Limitations

This systematic review is subject to several limitations. Firstly, only articles indexed in English were considered which might have caused a lack of information about cost in non-Englsih speaking countries. Secondly, a limited number of studies were identified for inclusion, and the included studies often contained small study populations. Moreover, the heterogeneity in study design and data collection methods suggests that the results may not be generalizable. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that the data cannot be generalized, particularly to non-high-income countries due to missing data. The variations in disease definitions and included cost components make data comparability challenging. Lastly, as only total costs were analysed, it is not possible to draw conclusions on specific cost drivers from this research.

Implications and conclusion

This systematic review offers valuable insights into the costs related to hypochondriasis while identifying relevant research gaps. However, it is important to note that the costs presented in this review are likely underestimated. This is primarily due to the variation in study methodology, where most studies only reported direct costs and employed different definitions of hypochondriasis or health anxiety, including various cost components. Establishing a comprehensive health care system with expanded therapy, prevention, or rehabilitation services relies on solid evidence. For this purpose, a guidance for a standardized and itemized cost survey is essential to identify potential cost drivers that can serve as targets for interventions. Future research especially for policy making should therefore seek to ascertain indirect costs on one hand, as it is likely that these add a significant burden to overall costs. On the other hand, we observed that there is a lack of uniformity of data collection and diagnostic criteria for the condition. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct further studies with consistent data collection and disease definitions.

To be able to assess the costs in a global context, low- and middle-income countries should also be the subject of further research, as only high-income countries have been considered so far. Furthermore, it is important to conduct research that examines the impact of health anxiety on the gross domestic product and the proportion of the total healthcare costs to underline the importance of appropriate interventions and possible savings through them. This could be particularly relevant as an increase in health anxiety in the form of cyberchondria as already explained in the introduction can also be expected in the future due to increasing digitalisation [9].

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- A&E:Accident and Emergency department

- BIB-CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Bibliotherapy

- DSM IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- GBP: Great British Pound

- G-ICBT: Therapist-Guided Internet Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- CC: Control Condition

- CONSORT: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- HA: Health Anxiety

- HAI: Health Anxiety Inventory\

- iACT: Internet-Delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- iCBT: Internet-Guided Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- iFORUM: Internet Forum

- ICD-11: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

- PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT: Randomised Controlled Trial

- RCBT: Remotely delivered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

- SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry

- SD: Standard Deviation

- SHAI: Short Health Anxiety Inventory

- ST: Somatization Threshold

- STROBE: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- TAU: Treatment as Usual

- U-ICBT: Unguided Internet Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

- WLC: Waiting List Control

References

Sunderland M, Newby JM, Andrews G. Health anxiety in Australia: prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service use. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(1):56–61.

Florian W, Samantha R, Julia MBN. Epidemiology of hypochondriasis and health anxiety: comparison of different diagnostic criteria. Curr Psychiatry Reviews. 2014;10(1):14–23.

Rask CU, Elberling H, Skovgaard AM, Thomsen PH, Fink P. Parental-reported health anxiety symptoms in 5- to 7-year-old children: the Copenhagen child cohort CCC 2000. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(1):58–67.

Eilenberg T, Frostholm L, Schröder A, Jensen JS, Fink P. Long-term consequences of severe health anxiety on sick leave in treated and untreated patients: analysis alongside a randomised controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;32:95–102.

Dziegielewski SF, DSM-IV-TR in Action. : John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated; 2010 [cited 2022 19.01.2022].

Olatunji BO, Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS. Is hypochondriasis an anxiety disorder? Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(6):481–2.

Bailer J, Kerstner T, Witthöft M, Diener C, Mier D, Rist F. Health anxiety and hypochondriasis in the light of DSM-5. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2016;29(2):219–39.

Axelsson E, Hedman-Lagerlof E. Cognitive behavior therapy for health anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical efficacy and health economic outcomes. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(6):663–76.

Tyrer P, Cooper S, Tyrer H, Wang D, Bassett P. Increase in the prevalence of health anxiety in medical clinics: possible cyberchondria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2019;65(7–8):566–9.

Loos A, Cyberchondria. Too much information for the Health anxious patient? J Consumer Health Internet. 2013;17(4):439–45.

Flessa S. Grundlagen Der Gesundheitsökonomik. In: Haring R, editor. Gesundheitswissenschaften. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2019. pp. 657–68.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

rayyan - intelligent systematic review [Web Page]. 2022 [cited 2022 18.04.2022]. Available from: https://www.rayyan.ai/.

Centre E. CCEMG - EPPI-Centre Cost Converter [cited 2022 19th January]. Available from: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/default.aspx.

Centre UE. EQUATOR network [cited 2022 19th January]. Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/.

The World Bank. The World by Income and Region [Internet] [cited 2022 January 19th]. Available from: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html#:~:text=The%20World%20Bank%20classifies%20economies,%2Dmiddle%2 C%20and%20high%20income.

Axelsson E, Andersson E, Ljotsson B, Hedman-Lagerlof E. Cost-effectiveness and long-term follow-up of three forms of minimal-contact cognitive behaviour therapy for severe health anxiety: results from a randomised controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2018;107:95–105.

Barsky AJ, Ettner SL, Horsky J, Bates DW. Resource utilization of patients with hypochondriacal health anxiety and somatization. Med Care. 2001;39(7):705–15.

Fink P, Ornbol E, Christensen KS. The outcome of health anxiety in primary care. A two-year follow-up study on health care costs and self-rated health. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(3):e9873.

Hedman E, Andersson E, Lindefors N, Andersson G, Ruck C, Ljotsson B. Cost-effectiveness and long-term effectiveness of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for severe health anxiety. Psychol Med. 2013;43(2):363–74.

Morriss R, Patel S, Malins S, Guo B, Higton F, James M, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of remotely delivered cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usual for repeat unscheduled care users with severe health anxiety: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):16.

Rask CU, Munkholm A, Clemmensen L, Rimvall MK, Ornbol E, Jeppesen P, et al. Health anxiety in preadolescence–Associated health problems, Healthcare Expenditure, and continuity in Childhood. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44(4):823–32.

Rimvall MK, Jeppesen P, Skovgaard AM, Verhulst F, Olsen EM, Rask CU. Continuity of health anxiety from childhood to adolescence and associated healthcare costs: a prospective population-based cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62(4):441–8.

Risor BW, Frydendal DH, Villemoes MK, Nielsen CP, Rask CU, Frostholm L. Cost effectiveness of Internet-Delivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Patients with severe health anxiety: a Randomised Controlled Trial. Pharmacoecon Open. 2022;6(2):179–92.

Seivewright H, Green J, Salkovskis P, Barrett B, Nur U, Tyrer P. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for health anxiety in a genitourinary medicine clinic: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(4):332–7.

Tyrer P, Cooper S, Salkovskis P, Tyrer H, Crawford M, Byford S, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):219–25.

Fink P, Ornbol E, Toft T, Sparle KC, Frostholm L, Olesen F. A new, empirically established hypochondriasis diagnosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(9):1680–91.

Fritz GK, Fritsch S, Hagino O. Somatoform disorders in children and adolescents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(10):1329–38.

Sharma D, Aggarwal AK, Downey LE, Prinja S. National Healthcare Economic Evaluation Guidelines: a Cross-country comparison. Pharmacoecon Open. 2021;5(3):349–64.

Andersen JS, Olivarius Nde F, Krasnik A. The Danish National Health Service Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):34–7.

Kasteler J, Kane RL, Olsen DM, Thetford C. Issues underlying prevalence of doctor-shopping behavior. J Health Soc Behav. 1976;17(4):329–39.

Konnopka A, Konig H. Economic burden of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. PharmacoEconomics. 2020;38(1):25–37.

Wright K, Hann N, McLeroy KR, Steckler A, Matulionis RM, Auld ME, et al. Health education leadership development: a conceptual model and competency framework. Health Promot Pract. 2003;4(3):293–302.

Health care issues of hypochondria, as viewed by a hypochondriac

I'm a hypochondriac. Here's how the health care system needs to deal with people like me

A late-night Flomax commercial is sometimes all it takes for me to start spinning in a cycle of anxiety. If I don’t need Flomax to help me pee better, then I imagine I probably need a screening for prostate cancer.

I’m a hypochondriac. I’m also a health care executive with insight into how the U.S. health care system works — and doesn’t work — which may contribute to my hyper focus on health.

People like me are often dismissed by family, friends, and many doctors. Hypochondria gets short shrift in the mental health space, obscured by the overarching and broad category of general anxiety disorder. Even in the post-Covid-19 era, where mental health has taken center stage, hypochondria — also known as illness anxiety — has yet to be given even a supporting role. The ripple effects of that require collective attention.

People with hypochondria put a significant burden on the health care system. The condition, characterized by a fixation on a fear of having a serious illness or dying, often leads individuals through a cascade of unnecessary medical tests and consultations. It is estimated that it costs the health care system hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

Insurance holders, both individual policyholders and companies providing benefits for their employees, feel the economic impact of this disorder on their costs, with overutilization eventually showing up in everyone’s increased copays and premiums, at great inequity to the average person.

A holistic approach to hypochondria

Frontline health care professionals must act in service to both their patients and the greater health care system as costs and resource run downhill quickly. And in an age of burnout, they must protect their own capacity (and faculties). Emergency room doctors are the first line of defense against people like me putting unneeded stress on the health care system. They must have a trained eye to spot hypochondria, a gentle touch to quell the mortal anxieties of those afflicted with it, and a firm resolve to deny superfluous care.

While hypochondriacs can tell you the names of the people staffing the emergency department as easily as the names of their kids, primary care also has a meaningful frontline role to play. As a group, people with hypochondria see their primary care clinicians far more often than the average person. This cohort knows who and what we are, and is best placed to influence our journeys.

If a person with hypochondria seeking care for something — but has no symptoms — is knowingly or unknowingly indulged by a health care professional, the journey could be down two destructive and costly paths: misdiagnosis or over-testing. Failing to diagnose hypochondria for what it is could perpetuate a cycle of fear and worry, increasing the likelihood of more doctor visits and more testing.

Changing the approach to identifying and treating hypochondria requires health care professionals to strike a challenging — but necessary — balance of thoroughly vetting their patients’ claims while remaining cautious of not overselling or recommending a battery of tests.

Fostering an environment of empathy and training health care providers (especially emergency doctors) to recognize and document people with hypochondria can close the gap in care between perceived and actual health concerns. Referrals to mental health professionals who treat hypochondria with cognitive behavioral therapy or medications the Food and Drug Administration has approved for treating hypochondria will create a realistic approach to addressing and validating people living with hypochondria.

What would also help is instituting a medical billing code for hypochondria. Without one, there is no way to diagnose and track outcomes of people frequenting the emergency department or primary care offices in search of reassurance and relief from anxiety.

In parallel, the health care industry needs to increase access to cutting-edge health care technology, such as full-body CT scans, which can detect in one sweep everything from broken bones to blood clots, infections, inflammation, and tumors. Such tools, along with personalized health monitoring devices, can provide individuals with the reassurance and clarity they need to proactively manage their health concerns.

Full disclosure: I paid out of pocket for my full-body CT scan. The results gave me great comfort. I fully recognize that the cost of full-body scans need to come down to be truly accessible (and believe that will happen given the history of competition) and understand that the procedure may not give everyone the comfort it gave me: Clear results made me feel like a weight had been lifted off my chest.

Equipping people with the means to understand and track their health indicators will reduce the psychological burden of uncertainty among many people with hypochondria. They — as well as people without this condition — will also benefit from an enhanced preventive care landscape, ultimately leading to a more efficient and cost-effective health care system.

The U.S. health care system broadly, and health care providers like emergency clinicians and primary care providers in particular, must work together to challenge the misinterpretation of hypochondria and illness anxiety that has led to a culture of misunderstanding and stigma and begin treating it properly. The question is, will that ever happen?

Hal Rosenbluth is the CEO of New Ocean Health Solutions, a digital health care company, and co-author with Marnie Hall of “Hypochondria: What’s Behind the Hidden Costs of Healthcare in America” (Rodin Books, June 18, 2024).

Comments

Post a Comment