Kiribati's Status in the Struggle between China's PRC and the West - In WW2 the weapons were blood, bombs and bullets - now it's Dollars and Yuan

Kiribati's Status in the Struggle between China's PRC and the West

In WW2 the weapons were blood, bombs and bullets - new it's Dollars and Yuan

Strategic importance: Despite its small population of about 130,000, Kiribati is strategically significant due to its location and vast exclusive economic zone. It's relatively close to Hawaii and controls over 3.5 million square kilometers of the Pacific Ocean.

Chinese influence:

- - China has promised to help Kiribati achieve its 20-year development plan (KV20).

- - There are reports of Chinese police officers working in Kiribati, purportedly in community policing and a crime database program.

- - China has plans to rebuild a World War II U.S. military airstrip on Kiribati's Kanton Island.

- - The scrapping of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area has reportedly led to an increase in Chinese fishing vessels in Kiribati's waters.

- - Relations with Australia have cooled, with Australian officials reporting visa denials or delays.

- - A bilateral strategic partnership agreement with Australia is indefinitely on hold.

- - President Maamau's decision to switch to China has been controversial domestically, causing rifts within his government.

- - There are concerns about lack of transparency in Kiribati's dealings with China.

- - The opposition fears China's influence on Kiribati's decision-making, including its temporary withdrawal from the Pacific Islands Forum in 2022.

- - The U.S. has pledged to upgrade a wharf on Kanton Island and expressed interest in opening an embassy in Kiribati.

- - Australia is working to meet Kiribati's security needs, including donating patrol boats and supporting police infrastructure upgrades.

7. Ongoing elections:

- - Kiribati is currently holding parliamentary elections, with presidential elections expected later in the year.

- - The elections are seen as potentially influencing the country's future alignment between China and the West.

8. Judicial crisis: There's an ongoing crisis in Kiribati's judiciary, with the suspension of foreign judges, which some observers link to the government's relationship with China.

In summary, Kiribati has become a focal point in the Pacific for the strategic competition between China and Western powers, particularly the U.S. and Australia. Its alignment with China since 2019 has raised concerns among Western allies about Beijing's growing influence in the region, while also causing internal political tensions within Kiribati itself.

History and Geography of Kiribati

Tarawa is a coral atoll of the Gilbert Islands and capital of Kiribati, in the west-central Pacific Ocean. It lies 2,800 miles (4,500 km) northeast of Australia and is the most populous atoll in the Gilberts.

World War 2

China Relations China PRC or Taiwan ROC

Kiribati, under the government of President Taneti Maamau, initially recognised the ROC but switched to PRC later on. From 1980 to 2003, Kiribati recognised the PRC. Relations between China and Kiribati then became a contentious political issue within Kiribati. President Teburoro Tito was ousted in a parliamentary vote of no confidence in 2003, over his refusal to clarify the details of a land lease that had enabled Beijing to maintain a satellite-tracking station in the country since 1997, and over Chinese ambassador Ma Shuxue's acknowledged monetary donation to "a cooperative society linked to Tito" In the ensuing election, Anote Tong won the presidency after "stirring suspicions that the station was being used to spy on US installations in the Pacific". Tong had previously pledged to "review" the lease.

An election in Kiribati provokes Western alarm about Beijing's sway in Pacific atoll nation | AP News

apnews.com

Updated 1:11 AM PDT, August 14, 2024

WELLINGTON, New Zealand (AP) — People in Kiribati went to the polls on Wednesday for the first round of voting in a national election expected to serve as a referendum on rising living costs and the government’s stronger ties with China.

A second round of voting is scheduled on Aug. 19 for all parliamentary seats that are not won by a majority vote on Wednesday. Results from the first round are expected Thursday.

The nation of low-lying atolls with 120,000 people is one of the most threatened in the world by rising sea levels and does not command the resource wealth or tourism branding of other Pacific islands. But its proximity to Hawaii and its huge ocean expanse have bolstered its strategic importance and provoked an influence skirmish between Western powers and Beijing.

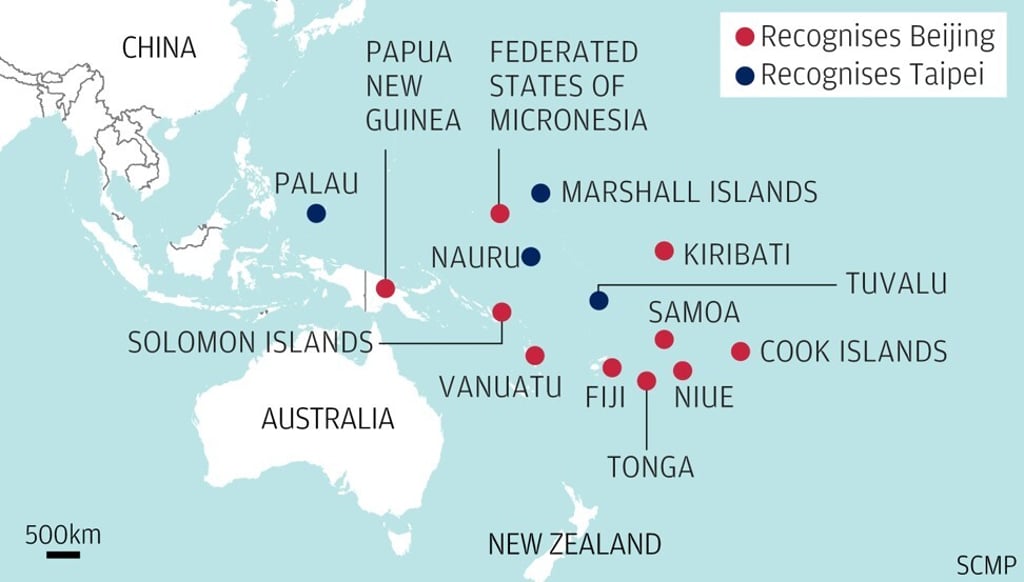

The Kiribati government switched its allegiance from pro-Taiwan to pro-Beijing in 2019, citing its national interest and joining several other Pacific nations that have severed diplomatic ties with Taipei since 2016.

Kiribati is one of the most aid-dependent nations in the world and is rated at high risk of external debt distress by the International Monetary Fund. Its existence is threatened by coastal erosion and rising seas that have contaminated drinking water and driven much of the population onto the most populous island, South Tarawa.

Analysts say few details about the campaigning or this week’s vote have appeared online and there are few English-language news sources in the country. The blocked or delayed entry of Australian officials to Kiribati and a stalled flow of information between the governments in recent years have prompted anxiety in Canberra about the scale of Beijing’s influence.

“A lot of countries in the region are really trying to find their place with a lot of geostrategic competition,” said Blake Johnson, a senior analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Kiribati has “taken the approach of keeping its cards pretty close” and is not divulging details “that might impact the way those relationships are trending,” he said.

The election will decide 44 of the 45 seats in Parliament but not the Kiribati presidency, which is due to be resolved in October. A public vote will be held to choose the leader from three or four candidates selected from among those elected this month.

The incumbent, Taneti Maamau, who has been in office since 2016, is expected to seek another term as leader if returned to his seat.

The increased cost of living, scarce medicine supplies and fuel shortages are expected to be central issues for voters. Analysts say voters are likely to reward the incumbent government for the introduction of universal unemployment benefits and increased subsidies for copra, or dried coconut flesh.

“People are taking time to link that the challenges they’re facing are a result of the policies that are in place,” Rimon Rimon, an independent journalist in Kiribati, said by phone. He said the prospect of incumbents being reelected was “quite strong at the moment.”

The question of how much influence Beijing has is not a simple one. Dismay from Australia, New Zealand and the United States about China’s sway is not always specific or well-articulated and has often caused frustration in the Pacific, Johnson said.

He said Australia’s worries include reports that Beijing has trained and equipped Kiribati police officers, and the suspension of foreign judges serving in the island nation.

“Interestingly, these Western countries maintain their own connections with China, but when small island states do the same, it suddenly raises concerns,” said Takuia Uakeia, director of the Kiribati campus of the University of the South Pacific. “This is well understood by the people.”

Rimon, the journalist, said policy shifts since Kiribati switched to a pro-Beijing stance include a requirement that researchers and reporters apply for permits for filming and a more “hard-line” approach to information access. The government remains very secretive about the content of 10 agreements signed between Kiribati and China in 2022, he added.

Voters who spoke by phone on Wednesday said a list of polling places had only been published by the government on Tuesday and there had been uncertainty before voting opened about whether identification cards were required to vote.

Political parties are loose groups in Kiribati, and lawmakers do not confirm their allegiance until elected to office. Kiribati was traditionally a society governed by consensus, with strong democratic principles and respect for its constitution, but the contest for foreign influence had sowed divisions, Rimon said.

“How we’re seeing things in terms of donors and cooperation with partners is that we’re not sure how this is helping us that they’re competing in this sense,” he said.

There are 115 candidates contesting the election, including 18 women. Candidates were unopposed for four seats — three of them incumbent lawmakers from the governing Tobwaan Kiribati Party, according to Radio New Zealand.

Kiribati votes in key election after years of turbulence

When Kiribati broke ties with Taipei in 2019, it was a blow to Taiwan, despite the Pacific island nation’s small stature on the international stage.

Taiwan had already lost six diplomatic allies to China in the years prior, including, just days earlier, the Solomon Islands, as Beijing stepped up its efforts to isolate the self-ruled democracy that it claims as its own.

Kiribati President Taneti Maamau’s decision to switch allegiance was also controversial at home, causing a rift within his own government and costing him his comfortable parliamentary majority in a fiercely fought election in 2020.

Senior figures in Kiribati, a low-lying atoll nation of about 130,000 people, feared a lack of transparency around Maamau’s relationship with China, which has previously formed debt-laden relationships with developing countries under its Belt and Road Initiative.

Five years since the switch, as Kiribati heads to the polls again, those fears persist following a turbulent period which has seen strained relations with Pacific neighbours, tensions with traditional ally Australia and a continuing constitutional crisis.

Banuera Berina, Maamau’s ally-turned-rival, who was his main opponent in 2020’s presidential election after splitting from the ruling Tobwaan Kiribati Party (TKP) over concern about its dealings with China, told Al Jazeera the relationship was “not healthy for the country”.

“Transparency is of paramount importance, which unfortunately is lacking in our government now,” said Berina, who is standing again as a parliamentary candidate, but does not plan to run for the presidency again.

While domestic issues such as the cost of living are set to dominate parliamentary elections this week and next, international observers will also be “watching closely” for any insight into the presidential elections later this year, according to Jessica Collins, a Pacific aid expert at the Lowy Institute.

“There’s a lot at stake. If the people vote for change, President Maamau may not get re-elected later in the year, frustrating China’s ambition and curtailing its successes,” she told Al Jazeera.

“If parliament – and later in the year the president – remains largely the same, Australia will have its work cut out trying to remain a valued and welcome partner,” she added.

‘Hoping for a reset’

On Wednesday, 114 candidates were contesting 44 seats in Kiribati’s parliament, Maneaba ni Maungatabu. A second round of voting is scheduled for August 19 to decide seats where no candidate has secured a majority.

Although political alignment is often clear, parliamentary candidates in Kiribati officially stand without party affiliation. Those elected to parliament then choose at least three candidates to be put forward for a presidential election, which is expected to take place in October.

Rimon Rimon, a local investigative journalist, said it was hard to gauge the mood in Kiribati because “people live in a landscape of fear”. But he said the vote would offer a “preview of what the people want” ahead of the presidential election.

While Rimon believes many people sense the governing party “has not been honest in their promises”, in a political system dominated by personal patronage over party affiliation, “well-resourced” government-aligned candidates might have the edge over the opposition.

“I think this whole election process is going in favour of the ruling party,” he told Al Jazeera.

A strong showing at the parliamentary elections for government-aligned candidates would boost Maamau’s campaign for a third successive presidential term, but some observers, like Rimon, worry about the consequences for Kiribati’s democratic future.

The past four years under the TKP have been among the most turbulent in Kiribati since the country gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1979.

In July 2022, Maamau withdrew Kiribati from the Pacific Islands Forum, citing his belief that the body, which plays a key role in regional cooperation on issues including security, economic development and climate change, was not serving his country’s interests.

While Maamau rejoined six months later, Kiribati’s opposition feared China played a role in the initial decision, suggesting that Beijing would benefit from an isolated Kiribati, not least in terms of security and exploiting the country’s fisheries. Beijing said the claim was “groundless”.

Kiribati is tiny but strategically significant. The closest of its 33 islands and atolls is just 2,160km (1,340 miles) south of Honolulu on the United States island of Hawaii.

China has promised to help Kiribati achieve KV20, a 20-year development plan launched by Maamau and structured around fishing and tourism. As part of that it has said it will help rebuild a World War II US military airstrip on Kiribati’s Kanton Island, which sits roughly halfway between Hawaii and Fiji.

In February, the Reuters news agency, citing the acting police chief, reported that Chinese police officers were working in Kiribati, taking part in community policing and a crime database programme under an agreement that has not been made public.

Kiribati also boasts one of the largest exclusive economic zones in the world, covering more than 3.5 million square kilometres of the equatorial Pacific – a pristine marine region roughly the size of India. The 2021 scrapping of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area, one of the world’s largest marine reserves and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has resulted in “Kiribati now hosting too many Chinese fishing vessels”, Berina said.

As ties have warmed with Beijing, Kiribati’s relations with traditional ally Canberra have cooled. Australian officials have reported that their visas have been denied or delayed, while a bilateral strategic partnership agreement, already a year overdue, has been put on ice indefinitely.

Blake Johnson, Pacific analyst at the government-funded Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), said the past four years had “seen the relationship between Australia and Kiribati decline” but that Canberra would be “hoping for a reset” even if Maamau got a third term.

“I would expect the Australian government to invest more time and effort into rebuilding that relationship,” he said.

‘No politics, no ideology’

Last May also saw judge David Lambourne, an Australian national who served in Kiribati’s High Court, forced out of the country following a years-long saga that has thrown the judiciary into crisis.

Maamau’s government first levelled charges of misconduct against Lambourne – a resident of Kiribati for three decades and husband of opposition politician Tessie Lambourne – in 2022. That year, attempts to deport Lambourne were deemed illegal by Kiribati’s Court of Appeal, composed of members of New Zealand’s judiciary.

Thwarted by expatriate judges, which have long formed the backbone of Kiribati’s high courts, Maamau’s government suspended Chief Justice William Hastings and the Appeal Court judges, causing the country’s judicial system to grind to a halt.

A senior source with close knowledge of Kiribati, who requested anonymity due to fears over his security, told Al Jazeera that the saga “completely compromised” the judiciary. The source added that “respect for democratic norms has deteriorated to such an extent that I don’t think it can be denied that the president is an autocrat”.

The source continued that the case against David Lambourne was a “blatant attack on the opposition” given his marriage to Tessie Lambourne, who is widely viewed as having the best chance of unseating Maamau in the presidential race.

While he did not think Beijing was providing explicit instructions to Maamau, the source said, “their interests certainly align” in wanting to “unseat Tessie Lambourne if they possibly could”.

“I imagine there are people in Beijing who would not want to see a change of government in Kiribati,” the source added.

A spokesman for President Maamau said he was not able to answer questions before publication. The Chinese embassy in Kiribati did not respond to Al Jazeera’s requests for comment however, ahead of the polls Ambassador Zhou Limin praised Maamau’s government and its “historic achievements in various areas”.

Einar Tangen, a senior fellow at the Taihe Institute in Beijing, paints a more benign and pragmatic picture of China’s relationship with Kiribati. He says the accusations of malevolent Chinese influence in Kiribati are part of the “same playbook” used by the US and Australia to discredit Beijing in other parts of the Pacific, and curtail its influence.

“There’s no politics [in the relationship], there’s no ideology. Kiribati has asked for help, and China has offered it,” he told Al Jazeera.

“Kiribati is not interested in the international politics of the US and China. They’re interested in food. They have one of the lowest GDPs per capita in the area and they’re trying to get on with their life. If somebody offers them more aid, they’re going to take it.”

‘An uphill battle’

Whether China is helping or not, several observers told Al Jazeera that the scales in the election appear tipped in the ruling party’s favour – not least in terms of financial resources.

Money, an important commodity in any election, becomes even more influential in a system in which ideology and party affiliation come second to personal patronage.

The anonymous source pointed to Tessie Lambourne’s constituency, the island of Abemama.

With two parliamentary seats up for grabs, Lambourne is competing against the current Minister for Infrastructure and Sustainable Energy, Willie Tokataake, and a previously unknown local school teacher, who has been “an extremely generous benefactor in the lead-up to the elections”.

While he cautioned that it was impossible to know for sure, the “generally understood view is that this money almost certainly originated in China and has been funnelled to him through the president’s political party”.

Journalist Rimon says several candidates have “raised eyebrows” because they are “splashing a lot of cash and giveaways for people”. “You just wonder, where are they getting all these resources? Why do they have so much money?” he said.

Berina alleged that when he was a TKP member, President Maamau promised that he and other parliamentarians would be “given money by China in order to retain our seats”.

Similar allegations were made in the last round of elections in 2020, with Maamau denying he received any financial support from China.

“There wasn’t any involvement especially in funding by the Chinese government,” he said in a rare interview with the media following his re-election.

China denies that it interferes in the internal affairs of Pacific nations.

Following a failed attempt to establish a Pacific-wide trade and security pact in 2022, Foreign Minister Wang Yi said China had “never established a so-called sphere of influence” and has “no intention of competing with anyone”.

Either way, Rimon believes Lambourne faces an “uphill battle” in this election. “She is on the top of the government’s list to try to eliminate, because if she doesn’t get re-elected in Abemama, that’s the end of [her presidential challenge],” he said.

From Beijing’s perspective, Collins of the Lowy Institute points to Lambourne’s “Australian connection” and her “deployment to Taiwan”, where she was Kiribati’s ambassador in 2018-19, as reasons for their possible concern.

“It’s possible for a Pacific nation to re-establish diplomatic relations with Taipei – a move that would grate against China given its reward-like investments in Kiribati when it switched allegiance to Beijing,” Collins said.

Berina, for his part, said he will support any opposition candidate, including Tessie Lambourne, given his “grave concerns” over Maamau’s closeness with China.

“The danger lies in the fact that we are being made to walk in the dark,” he said. “And in the dark, you can never know the kind of danger lurking therein.”

Exclusive: Chinese police work in Kiribati, Hawaii's Pacific neighbour

SYDNEY, Feb 23 (Reuters) - Chinese police are working in the remote atoll nation of Kiribati, a Pacific Ocean neighbour of Hawaii, with uniformed officers involved in community policing and a crime database program, Kiribati officials told Reuters.

Kiribati has not publicly announced the policing deal with China, which comes as Beijing renews a push to expand security ties in the Pacific Islands in an intensifying rivalry with the United States.

Kiribati, a nation of 115,000 residents, is considered strategic despite being small, as it is relatively close to Hawaii and controls one of the biggest exclusive economic zones in the world, covering more than 3.5 million square kilometres (1.35 million square miles) of the Pacific. It hosts a Japanese satellite tracking station.

Kiribati's acting police commissioner Eeri Aritiera told Reuters the Chinese police on the island work with local police, but there was no Chinese police station in Kiribati.

"The Chinese police delegation team work with the Kiribati Police Service - to assist on Community Policing program and Martial Arts (Tai Chi) Kung Fu, and IT department assisting our crime database program," he said in an email.

China's embassy in Kiribati did not respond to a Reuters request for comment on the role of its police. In a January social media post the embassy named the leader of "the Chinese police station in Kiribati".

Aritiera, who attended a December meeting between China's public security minister Wang Xiaohong and several Pacific Islands police officials in Beijing, said Kiribati had requested China's policing assistance in 2022.

Up to a dozen uniformed Chinese police arrived last year on a six month rotation.

"They only provide the service that the Kiribati Police Service needs or request," Aritiera said.

The Kiribati president's office did not respond to a request for comment.

CHINA SEEKS POLICING TIES

China's efforts to strike a region-wide security and trade deal in the region, where it is a major infrastructure lender, were rejected by the Pacific Islands Forum in 2022.

However, Chinese police have deployed in the Solomon Islands since 2022, after the two nations signed a secret security pact criticised by Washington and Canberra as undermining regional stability.

Australian National University's Pacific expert Graeme Smith said China was seeking to extend its reach over the Chinese diaspora, and police were "very useful eyes and ears" abroad.

"It is about extraterritorial control," he said. Chinese police would also "have eyes on Kiribati's domestic politics and its diplomatic partners".

Aritiera said the Chinese police were not involved in security for Chinese citizens on the island.

China's ambassador to Australia said last month that China had a strategy to form policing ties with Pacific Island countries to help maintain social order and this should not cause Australia anxiety.

Kiribati switched ties from Taiwan to Beijing in 2019, with President Taneti Maamau encouraging Chinese investment in infrastructure. It will hold a national election this year.

China built a large embassy on the main island and sent agricultural and medical teams. It also announced plans to rebuild a World War Two U.S. military airstrip on Kiribati's Kanton Island, prompting concern in Washington. The airstrip has not been built.

At its closest point, Kiribati's Kiritimati island is 2,160 km (1,340 miles) south of Honolulu.

The United States countered with a pledge in October to upgrade the wharf on Kanton island, a former U.S. military base, and said it wants to open an embassy in Kiribati.

Director of the Lowy Institute's Pacific Islands Program, Meg Keen, said China had security ambitions in the region.

"Australia and the United States are concerned about that prospect, in Kiribati and around the region, and are taking measures to protect their position," she said.

A spokeswoman for Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs said Australia was working to meet Kiribati's security needs and had donated two patrol boats.

"Australia is supporting the Kiribati Police Service with major upgrades to its policing infrastructure, including a new barracks and headquarters and radio network," she said.

Papua New Guinea, the biggest Pacific Island nation, said this month it would not accept a Chinese offer of police assistance and surveillance technology, after news it was negotiating a policing deal with China prompted criticism from traditional security partners, the United States and Australia.

The Reuters Daily Briefing newsletter provides all the news you need to start your day. Sign up here.

Reporting by Kirsty Needham; Editing by Sonali Paul

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles., opens new tab

Comments

Post a Comment