UC System Faces a Cloudy Future with Contrary Winds Expected

|

| Three Decade Trends in UC Applicants, Admits, and Enrollees |

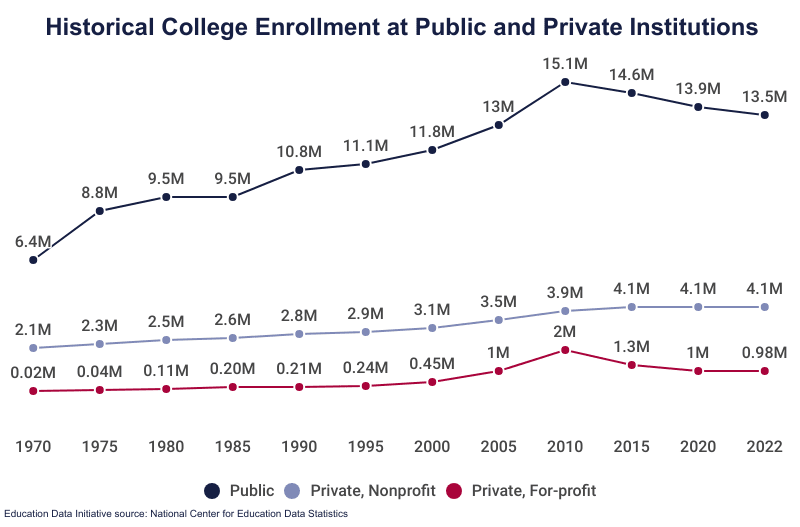

UC System Faces a Cloudy Future with Contrary Winds ExpectedThe University of California's ambitious $30 billion expansion program appears strategically sound despite projected demographic declines, primarily due to increasing college preparation rates among high school graduates and the system's unique position to serve historically underrepresented regions, according to a comprehensive analysis of enrollment and capacity data.

While California's overall college enrollment is expected to plateau and then decline after 2035, UC specifically is projected to maintain robust growth, driven by a dramatic increase in the percentage of high school students completing college preparatory requirements – from 37% to 52% over the past decade.

"This isn't just about adding seats – it's about strategic growth where it's needed most," said [would cite expert here]. Nearly two-thirds of UC's projected expansion will occur at UC Merced and UC Riverside, specifically targeting the underserved San Joaquin Valley and Inland Empire regions.

The expansion comes as the system faces critical infrastructure needs, with many campus buildings dating to the 1950s and 1960s requiring $16 billion in seismic retrofits. These safety and modernization requirements would need to be addressed regardless of enrollment growth, making the timing appropriate for comprehensive campus improvements.

UC's 2030 Capacity Plan outlines two growth scenarios: a base plan to add 23,000 state-supported undergraduate students and an aspirational goal of 33,000 additional students. Unlike community colleges, which are more dependent on local demographics, UC's ability to draw students from across California helps insulate it from regional population shifts.

The system is also taking steps to maximize existing capacity through increased online and summer offerings, improved graduation rates, and enhanced transfer pathways from community colleges. These efficiency measures complement physical expansion plans.

However, significant challenges remain. The system hasn't received state General Obligation bonds since 2006, forcing reliance on a complex mixture of funding sources including loans, private investment, and student fees. Current budget uncertainties and local opposition to campus expansion projects could also impact implementation timelines.

Housing remains a particular concern, with the system currently accommodating 40% of students. While new housing projects can be self-funding through future rent revenues, several campuses have stressed the need to align enrollment growth with additional bed spaces.

The expansion faces additional hurdles at some of the system's most popular campuses. UC Berkeley, for example, projects growth of 8,100 students through 2036 but faces capacity constraints, strict local sustainability goals, and neighborhood opposition that may limit increases.

Multiple infrastructure projects are legally mandated, particularly seismic upgrades to medical facilities, making some aspects of the expansion non-discretionary. The system's medical facilities represent a significant portion of the construction plans.

Looking ahead, UC's ability to execute its expansion will depend heavily on securing sustainable funding sources and potentially accelerating alternative growth strategies. While demographic trends suggest challenges for higher education broadly in California, UC's specific market position and strategic focus on underserved regions appear to justify its ambitious plans.

1. Demographic & Enrollment Projections:

- - Overall college enrollment in CA will increase slightly through 2035, then decline

- - UC specifically is projected to see robust enrollment growth due to:

- - Increasing A-G completion rates (up from 37% to 52% of HS graduates)

- - Strong student demand, especially at selective campuses

- - System's ability to draw students from across regions

- - Unlike community colleges, UC is less vulnerable to local population changes

- - Critical seismic and modernization needs remain valid regardless of enrollment:

- - Many buildings from 1950s/60s require upgrades

- - $16B in seismic retrofits needed for safety/compliance

- - UC has legal obligations to strengthen medical facilities

- - Housing expansion is strategic:

- - Currently houses 40% of students

- - Housing capacity helps attract/retain students in expensive markets

- - Housing projects can be self-funding through rents

- - UC's 2030 Capacity Plan has two scenarios:

- - Base: Add 23,000 state-supported undergraduate FTE students

- - Aspirational: Add 33,000 state-supported undergraduate FTE students

- - Growth focused strategically on:

- - UC Merced and UC Riverside (65% of projected growth)

- - Expanding access in underserved San Joaquin Valley and Inland Empire

- - Complemented by efficiency measures:

- - Increased online/summer offerings

- - Improved graduation rates

- - Enhanced transfer pathways

- - Funding challenges are significant:

- - No state General Obligation bonds since 2006

- - Complex blend of funding needed (bonds, loans, private investment, fees)

- - Current budget uncertainty may impact near-term support

- - But UC has more diverse funding options than CSU/CCC:

- - Greater access to philanthropy

- - More revenue-generating opportunities

- - Stronger borrowing capacity

Conclusion:

The UC expansion actually appears justified, despite demographic headwinds. The growth is:- Demand-Driven: Increasing A-G completion rates and strong applications suggest sustained demand for UC specifically, even as overall college enrollment may plateau

- Strategically Targeted: Focus on underserved regions and campuses with room to grow, rather than just expanding already-impacted campuses

- Infrastructure-Justified: Many projects address critical safety and modernization needs that exist regardless of enrollment growth

- Equity-Enhancing: Expansion plans could help close geographic and demographic gaps in UC access

- - Uncertain state funding support

- - Need for sustainable financing mechanisms

- - Local opposition/CEQA challenges at some campuses

- - Housing capacity constraints

UC faces half-billion-dollar budget shortfall and increases tuition for new nonresident students | KPBS Public Media

The University of California is eyeing a looming budget gap of half a billion dollars next year. To help balance the books it’s relying in part on its out-of-state undergraduates.

Meanwhile, the system is pouring tens of billions of dollars into construction projects for seismic retrofitting, new classrooms and medical centers — while also acknowledging it lacks the funding to build or renovate most of what it needs.

Out-of-state undergraduates at the UC are charged more than three times the total tuition in-state students are expected to pay. Now system leaders have increased the supplemental tuition for new non-resident undergraduates by $3,402 next fall, an amount that’s $2,208 more than what the supplemental tuition would increase by under existing UC policy.

A UC regents committee approved the new hike Wednesday; the full board voted to greenlight the measure today.

One regent, Jose M. Hernandez, voted no. Two elected state leaders on the board, Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis and Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas, abstained from voting.

“I just want to be on the record opposing the tuition increase, and also on the record recognizing the commitment of staff to continue to work to evaluate and understand these decisions to increase the cost of attendance for out of state students,” Kounalakis said today.

Under a model passed in 2021, each new cohort of undergraduates sees higher tuition and fees than the previous crop of new students but that tuition stays flat for their time at the UC. In-state students are charged tuition and a systemwide fee. Out-of-state students are charged that plus a much larger supplemental fee. The base tuition and fee would go up as planned under the 2022 model; only the supplemental fee would rise at a higher than expected amount.

All told, it would mean new nonresident undergraduates would pay $52,536 in total mandatory tuition next fall, excluding separate campus fees that are an average of $1,700. Current new nonresident undergraduates pay $48,636 annually, plus campus fees.

The move would affect the roughly 15% of UC undergraduates, including transfer students, who live outside of California and will begin their studies at the university system next fall. The increase wouldn’t affect current students or future graduate students.

“As UC prepares for an anticipated state budget cut that could impact student services across the entire system, we are proposing an increase to support core operations without raising costs for current students and California residents,” wrote UC spokesperson Omar Rodriguez in an email.

“Opportunity to higher education should not face any more barriers. Instead of increasing the salaries of UC administrators, let’s make sure college is more affordable for all.”Eduardo Tapia Jr-Urbieta, executive officer for the UC Student Association

The hike would increase revenue by about $41 million for the system annually, Rodriguez wrote.

The impending half-billion shortfall next summer would occur if state lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom make good on a deal to delay previously promised new money for the UC and apply a cut to its state support.

UC’s operating revenue is estimated to be about $53 billion in 2024-25. Most of that is from the system’s medical services work, including hospitals. Its core mission of educating students, largely faculty salary and benefits as well as financial aid, makes up about $11 billion of the system’s budget. That amount is almost evenly paid for with state dollars and a combination of tuition revenue and other university funds.

It’s among the numerous fiscal details that emerged at the regents’ regularly scheduled November meeting, including the revelation that the UC plans to spend $30 billion to repair or replace its increasingly aging stock of academic buildings, medical centers and dorms by decade’s end. And yet, that massive sum falls far short of the 10-campus system’s stated construction needs — a total of $53 billion in projects without a funding source.

The building spree is occurring as UC trundles toward a goal of adding 23,000 new California students by 2030 — fueled in part by lawmaker demands that the vaunted system make space for more California high schoolers.

The tuition hike in context

In some ways the emphasis on out-of-state students is a return to form for the UC, which both relies on these students for the much higher tuition they pay but also is under pressure by lawmakers to limit how many non-Californian undergraduates the system enrolls.

Eduardo Tapia Jr-Urbieta, an executive officer for the UC Student Association, which represents undergraduate students, said that the student association opposes the increase. “Opportunity to higher education should not face any more barriers. Instead of increasing the salaries of UC administrators, let’s make sure college is more affordable for all,” he told regents yesterday.

Those September raises came in two waves: 4.2% for senior UC officials, such as the system president and most campus chancellors, and extra raises, including for most of the chancellors — ranging from 16% to 33%. The extra chancellor raises are paid with private donations, not tuition or state support. The updated chancellor salaries range from $785,000 to nearly $1.2 million

Nonresident undergraduate students tend to have higher family incomes than resident students. In 2021, 45% of nonresident undergraduates had family incomes of above $185,000. The same was true for 25% of undergraduates from California. Nearly three-quarters of nonresident undergraduates came from households exceeding $93,000; for California-based undergrads, it was 45%.

Still, nonresident students on average pay much more to attend a UC campus, even after all financial aid is factored into their costs. The net price — which includes tuition, housing and other related costs minus grants and scholarships — for resident undergraduates with household incomes above $180,000 was around $37,000 a year last fall. For nonresident undergraduates, the average net price was $67,000.

“I support it (the nonresident tuition increase). I’ll get pushback for that, but here we are,” said Josiah Beharry, a student regent who can cast a vote on the board.

UC officials said that compared to some other major public universities, UC’s nonresident undergraduates pay lower nonresident fees. For example, University of Michigan nonresident students paid $11,500 more than their nonresident UC peers in 2023-24. University of Virginia nonresident undergraduate paid $7,000 more. Even when adjusting for living costs, nonresident Californians are charged less for their education, UC officials said.

UC policy permits 20% of new nonresident tuition revenue to be reserved for financial aid for nonresident undergraduates.

$30 billion in planned construction

The $30 billion construction plan — and $50 billion in projects without a funding source — were spelled out in a new, 207-page report detailing construction plans that UC budget officials presented to the system’s regents yesterday.

“The University’s enrollment growth and continuing needs for renewal, modernization and seismic correction of existing facilities are the key drivers of capital investments,” the report said.

Cranes have been soaring above the system’s campus skylines for years.

Since 2011, the UC has added beds for 42,000 students, growing from nearly 75,000 beds. The increase means the system can house 40% of its students, up from 32% a decade ago.

And UC isn’t done as it’s on track to build dorm space for 14,000 new beds at all nine undergraduate-serving campuses through 2030 — at a cost of $6.9 billion. That’s nearly half-a-million-dollars per bed.

But while student housing projects can largely pay for themselves over time through the rents campuses charge, classroom buildings have fewer sources of cash beyond system bonds and state dollars — which the UC says are hardly enough to meet campus needs.

Take for example all the seismic repairs UC says it must undergo to extend the life of its buildings, with structures built in the 1950s and 1960s representing the largest chunk of UC’s gargantuan building footprint. UC has $16 billion in seismic retrofit needs but only identified funding for 16% of that, or $2.5 billion, last academic year.

“I support it (the nonresident tuition increase). I’ll get pushback for that, but here we are.”Josiah Beharry, UC student regent

It’s not just finding money that’s a concern for UC. As buildings undergo remodeling, the classrooms, research and other activity core to the system’s mission has to continue. “The scope and complexity of planning required to minimize these disruptions can often necessitate the construction of temporary or replacement space,” the report read.

The scale of the need is vast. According to the UC, about 1,464 buildings require seismic upgrades across the system.

UC officials disclosed yesterday that the system is debuting a new plan in which campuses will reduce its backlog of structures that need seismic upgrades by 4% annually, with the structures most in need of an overhaul receiving priority.

And then there’s all the new construction UC needs. The system completed 139 projects at a cost of $1.4 billion last academic year — but has more than $20 billion in active construction plans for about 400 projects. More than half of those are for UC’s extensive medical care operation, in part to satisfy state rules on strengthening hospitals to better withstand earthquakes.

Through 2030, UC’s construction plans total $30 billion, with about $12 billion for its medical centers. Philanthropy helps pay for all those projects, but only a little. Just about $2 billion of the construction plan budget will come from gifts. About $300 million will come from state funds directly — a relatively tiny portion of the overall revenue picture for the system’s six-year building plan. Much of the projects will be paid for with external financing, such as bonds that the system sells to investors.

But that’s just projects with a funding source. UC Berkeley, for example, has more than $14 billion in construction needs but has identified the funding for just about $2.8 billion of that.

What is getting built at the system’s oldest campus? For starters, a new undergraduate academic building that’ll include 27 classrooms and a 400-seat auditorium with a rooftop terrace. All of that costs $137 million. It’s scheduled to open in the 2025-26 academic year.

Tuition & cost of attendance

Going to college is an investment - but it’s worth it. We have generous financial aid programs and predictable tuition costs year-to-year that help to bring a UC education within reach.

Nearly 70% of our California undergrads get an average of $20,000 in grants and scholarships to help with costs, including UC tuition, food and housing, transportation, books and supplies.

Even if you don’t qualify for financial aid, UC’s Tuition Stability Plan keeps your tuition the same for up to six years. Tuition stability applies to both California resident and nonresident students and helps you plan for the total cost of your UC education.

Estimated average costs for California residents, 2025–26

This chart estimates the cost of attending UC for one year as a new California resident undergraduate. For a significant proportion of our students, these expenses are offset by grants and scholarships.

Keep in mind that your total cost will vary depending on your personal expenses and the campus you attend.

| Direct costs | On campus | Off campus |

| UC Tuition | $14,934 | $14,934 |

| Campus fees | $1,700 | $1,700 |

| Campus housing and meals | $20,500 | |

| Health insurance allowance/fee | $3,500 | $3,500 |

| Total direct costs | $40,634 | $20,134 |

|

|

||

| Indirect costs | On campus | Off campus |

| Books and supplies | $1,400 | $1,400 |

| Housing & meals | $18,000 | |

| Personal transportation | $3,200 | $4,100 |

| Total indirect costs | $4,600 | $23,500 |

|

|

||

| TOTAL COST (direct and indirect) | $45,234 | $43,634 |

* UC Tuition remains flat for up to six years under the Tuition Stability Plan. It includes systemwide tuition (the cost of classes for California resident students), and student services fees for areas such as student government, student public transportation, and building improvements. These fees are set regardless of the method of instruction and will not be refunded in the event instruction occurs remotely for any part of the academic year.

Estimated average costs for nonresidents, 2025–26

This chart estimates the cost of attending UC for one year as a new nonresident undergraduate. UC tuition includes $34,200 in nonresident supplemental tuition. Keep in mind that your total cost will vary depending on your personal expenses and the campus you attend.

| Direct costs | On campus | Off campus |

| UC Tuition | $50,328 | $50,328 |

| Campus fees | $1,700 | $1,700 |

| Campus housing and meals | $20,500 | |

| Health insurance allowance/fee | $3,500 | $3,500 |

| Total direct costs | $76,028 | $55,528 |

|

|

||

| Indirect costs | On campus | Off campus |

| Books and supplies | $1,400 | $1,400 |

| Housing & meals | $18,000 | |

| Personal transportation | $3,200 | $4,100 |

| Total indirect costs | $4,600 | $23,500 |

|

|

||

| TOTAL COST (direct and indirect) | $80,628 | $79,028 |

* UC Tuition remains flat for up to six years under the Tuition Stability Plan. For non-residents, this includes systemwide tuition (the cost of classes for CA resident students), supplemental nonresident tuition, and student services fees for areas such as student government, student public transportation, and building improvements. These fees are set regardless of the method of instruction and will not be refunded in the event instruction occurs remotely for any art of the academic year.

Understanding California residency

If you're not sure whether you're a resident or a nonresident, review the policies:

California residence for the purposes of tuition and fees »

Good to know

Obtaining California residency for the purposes of tuition and fees is extremely difficult for undergraduates with nonresident parents (this includes transfer students from community colleges and other postsecondary institutions within California).

Virtually all nonresident undergraduates with nonresident parents remain nonresidents for the duration of their undergraduate career at UC.

UC faces half-billion-dollar budget shortfall and increases tuition for new nonresident students

In summary

The University of California anticipates more than a $500 million budget gap next summer, so It’s increasing tuition by at least $3,402 for new nonresident students next fall. Meanwhile, the system is planning billions in construction projects.

The University of California is eyeing a looming budget gap of half a billion dollars next year. To help balance the books it’s relying in part on its out-of-state undergraduates.

Meanwhile, the system is pouring tens of billions of dollars into construction projects for seismic retrofitting, new classrooms and medical centers — while also acknowledging it lacks the funding to build or renovate most of what it needs.

Out-of-state undergraduates at the UC are charged more than three times the total tuition in-state students are expected to pay. Now system leaders have increased the supplemental tuition for new non-resident undergraduates by $3,402 next fall, an amount that’s $2,208 more than what the supplemental tuition would increase by under existing UC policy.

A UC regents committee approved the new hike Wednesday; the full board voted to greenlight the measure today.

One regent, Jose M. Hernandez, voted no. Two elected state leaders on the board, Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis and Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas, abstained from voting.

“I just want to be on the record opposing the tuition increase, and also on the record recognizing the commitment of staff to continue to work to evaluate and understand these decisions to increase the cost of attendance for out of state students,” Kounalakis said today.

Under a model passed in 2021, each new cohort of undergraduates sees higher tuition and fees than the previous crop of new students but that tuition stays flat for their time at the UC. In-state students are charged tuition and a systemwide fee. Out-of-state students are charged that plus a much larger supplemental fee. The base tuition and fee would go up as planned under the 2022 model; only the supplemental fee would rise at a higher than expected amount.

All told, it would mean new nonresident undergraduates would pay $52,536 in total mandatory tuition next fall, excluding separate campus fees that are an average of $1,700. Current new nonresident undergraduates pay $48,636 annually, plus campus fees.

The move would affect the roughly 15% of UC undergraduates, including transfer students, who live outside of California and will begin their studies at the university system next fall. The increase wouldn’t affect current students or future graduate students.

“As UC prepares for an anticipated state budget cut that could impact student services across the entire system, we are proposing an increase to support core operations without raising costs for current students and California residents,” wrote UC spokesperson Omar Rodriguez in an email.

“Opportunity to higher education should not face any more barriers. Instead of increasing the salaries of UC administrators, let’s make sure college is more affordable for all.”

Eduardo Tapia Jr-Urbieta, executive officer for the UC Student Association

The hike would increase revenue by about $41 million for the system annually, Rodriguez wrote.

The impending half-billion shortfall next summer would occur if state lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom make good on a deal to delay previously promised new money for the UC and apply a cut to its state support.

UC’s operating revenue is estimated to be about $53 billion in 2024-25. Most of that is from the system’s medical services work, including hospitals. Its core mission of educating students, largely faculty salary and benefits as well as financial aid, makes up about $11 billion of the system’s budget. That amount is almost evenly paid for with state dollars and a combination of tuition revenue and other university funds.

It’s among the numerous fiscal details that emerged at the regents’ regularly scheduled November meeting, including the revelation that the UC plans to spend $30 billion to repair or replace its increasingly aging stock of academic buildings, medical centers and dorms by decade’s end. And yet, that massive sum falls far short of the 10-campus system’s stated construction needs — a total of $53 billion in projects without a funding source.

The building spree is occurring as UC trundles toward a goal of adding 23,000 new California students by 2030 — fueled in part by lawmaker demands that the vaunted system make space for more California high schoolers.

The tuition hike in context

In some ways the emphasis on out-of-state students is a return to form for the UC, which both relies on these students for the much higher tuition they pay but also is under pressure by lawmakers to limit how many non-Californian undergraduates the system enrolls.

Eduardo Tapia Jr-Urbieta, an executive officer for the UC Student Association, which represents undergraduate students, said that the student association opposes the increase. “Opportunity to higher education should not face any more barriers. Instead of increasing the salaries of UC administrators, let’s make sure college is more affordable for all,” he told regents yesterday.

Those September raises came in two waves: 4.2% for senior UC officials, such as the system president and most campus chancellors, and extra raises, including for most of the chancellors — ranging from 16% to 33%. The extra chancellor raises are paid with private donations, not tuition or state support. The updated chancellor salaries range from $785,000 to nearly $1.2 million

Nonresident undergraduate students tend to have higher family incomes than resident students. In 2021, 45% of nonresident undergraduates had family incomes of above $185,000. The same was true for 25% of undergraduates from California. Nearly three-quarters of nonresident undergraduates came from households exceeding $93,000; for California-based undergrads, it was 45%.

Read Next

Still, nonresident students on average pay much more to attend a UC campus, even after all financial aid is factored into their costs. The net price — which includes tuition, housing and other related costs minus grants and scholarships — for resident undergraduates with household incomes above $180,000 was around $37,000 a year last fall. For nonresident undergraduates, the average net price was $67,000.

“I support it (the nonresident tuition increase). I’ll get pushback for that, but here we are,” said Josiah Beharry, a student regent who can cast a vote on the board.

UC officials said that compared to some other major public universities, UC’s nonresident undergraduates pay lower nonresident fees. For example, University of Michigan nonresident students paid $11,500 more than their nonresident UC peers in 2023-24. University of Virginia nonresident undergraduate paid $7,000 more. Even when adjusting for living costs, nonresident Californians are charged less for their education, UC officials said.

UC policy permits 20% of new nonresident tuition revenue to be reserved for financial aid for nonresident undergraduates.

$30 billion in planned construction

The $30 billion construction plan — and $50 billion in projects without a funding source — were spelled out in a new, 207-page report detailing construction plans that UC budget officials presented to the system’s regents yesterday.

“The University’s enrollment growth and continuing needs for renewal, modernization and seismic correction of existing facilities are the key drivers of capital investments,” the report said.

Cranes have been soaring above the system’s campus skylines for years.

Since 2011, the UC has added beds for 42,000 students, growing from nearly 75,000 beds. The increase means the system can house 40% of its students, up from 32% a decade ago.

And UC isn’t done as it’s on track to build dorm space for 14,000 new beds at all nine undergraduate-serving campuses through 2030 — at a cost of $6.9 billion. That’s nearly half-a-million-dollars per bed.

But while student housing projects can largely pay for themselves over time through the rents campuses charge, classroom buildings have fewer sources of cash beyond system bonds and state dollars — which the UC says are hardly enough to meet campus needs.

Take for example all the seismic repairs UC says it must undergo to extend the life of its buildings, with structures built in the 1950s and 1960s representing the largest chunk of UC’s gargantuan building footprint. UC has $16 billion in seismic retrofit needs but only identified funding for 16% of that, or $2.5 billion, last academic year.

“I support it (the nonresident tuition increase). I’ll get pushback for that, but here we are.”

Josiah Beharry, uc student regent

It’s not just finding money that’s a concern for UC. As buildings undergo remodeling, the classrooms, research and other activity core to the system’s mission has to continue. “The scope and complexity of planning required to minimize these disruptions can often necessitate the construction of temporary or replacement space,” the report read.

The scale of the need is vast. According to the UC, about 1,464 buildings require seismic upgrades across the system.

UC officials disclosed yesterday that the system is debuting a new plan in which campuses will reduce its backlog of structures that need seismic upgrades by 4% annually, with the structures most in need of an overhaul receiving priority.

And then there’s all the new construction UC needs. The system completed 139 projects at a cost of $1.4 billion last academic year — but has more than $20 billion in active construction plans for about 400 projects. More than half of those are for UC’s extensive medical care operation, in part to satisfy state rules on strengthening hospitals to better withstand earthquakes.

Through 2030, UC’s construction plans total $30 billion, with about $12 billion for its medical centers. Philanthropy helps pay for all those projects, but only a little. Just about $2 billion of the construction plan budget will come from gifts. About $300 million will come from state funds directly — a relatively tiny portion of the overall revenue picture for the system’s six-year building plan. Much of the projects will be paid for with external financing, such as bonds that the system sells to investors.

But that’s just projects with a funding source. UC Berkeley, for example, has more than $14 billion in construction needs but has identified the funding for just about $2.8 billion of that.

What is getting built at the system’s oldest campus? For starters, a new undergraduate academic building that’ll include 27 classrooms and a 400-seat auditorium with a rooftop terrace. All of that costs $137 million. It’s scheduled to open in the 2025-26 academic year.

College Enrollment Statistics [2024]: Total + by Demographic

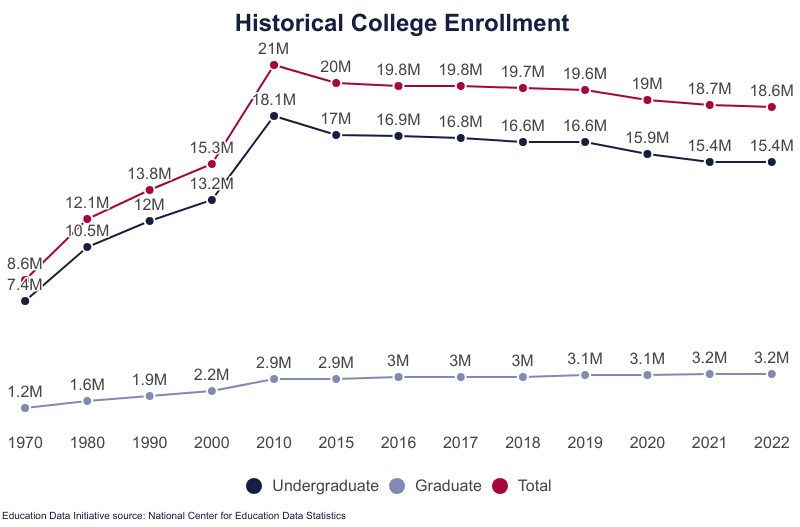

Report Highlights. College enrollment totaled 15.397 million undergraduate students nationwide in fall 2022, a 7% decline from 2019.

- The number of total enrolled postsecondary students declined by 0.4% from 2021 to 2022.

- 17.13% of all postsecondary students are in graduate programs.

- Preliminary data indicate that total postsecondary enrollment in Spring 2024 increased by 2.6% over the past year.

- 20.35% of the student population is Hispanic or Latino, a 483% increase from 1976.

- The number of female college attendance has nearly doubled since 1976, increasing by 82.9%.

A further 371,359 students attend postsecondary institutions that do not, at the time of publication, grant degrees; most of these institutions are transitioning to higher levels of education. Students at these institutions are excluded from this report unless noted otherwise. When including these students, the nationwide total number of postsecondary students climbs to 18.95 million as of Fall 2022.

Related research reports include Student Loan Debt Statistics | College Graduation Statistics | College Dropout Rates | Average Cost of College | Student Loan Refinancing

College Enrollment Statistics

College enrollment statistics indicate that more Americans are forgoing higher education; some may be putting off college attendance to build savings.

- Enrollment peaked in 2010 at 21.02 million.

- Since 2010, enrollment has declined 11.61%.

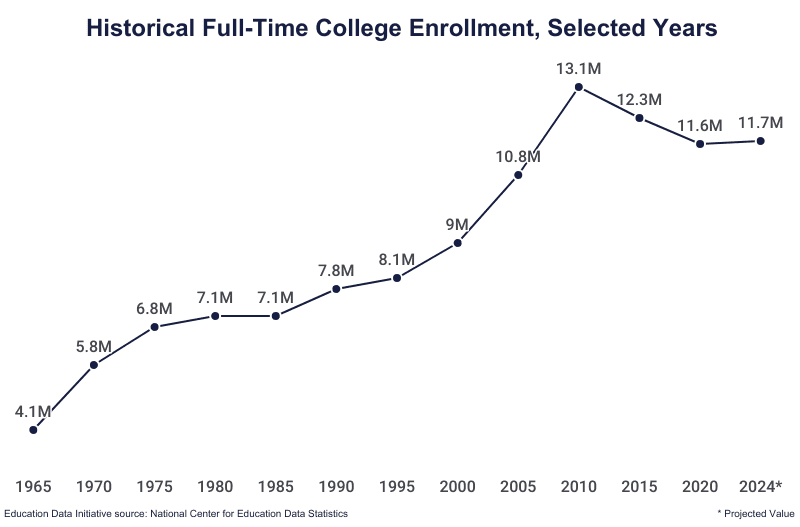

- 11.29 million or 60.7% of all students, graduate and undergraduate, are enrolled full-time.

- 62% of high school (or equivalent) graduates go on to postsecondary study.

- The rate of enrollment among new high school graduates declined 7.1% since 2018.

- Since 1960, the percentage of recent high school graduate enrollment increased by 16.9% in total.

- Among first-time, first-year college students, 82.68% are full-time students.

- As many as 5.52% of American adults are currently enrolled in college as part-time or full-time students.

- In the 2022-2023 academic year, 1,057,188 enrolled students were foreign-born.

| Year | Total Enrollment | % Public Institution Enrollment |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 (Projected) | 19,247,640 | 73.19% |

| 2023 (Projected) | 18,939,568 | 73.19% |

| 2022 | 18,580,026 | 72.63% |

| 2021 | 18,658,756 | 72.60% |

| 2020 | 19,027,410 | 72.97% |

| 2019 | 19,630,178 | 73.88% |

| 2018 | 19,651,412 | 73.99% |

| 2017 | 19,778,151 | 73.68% |

| 2016 | 19,846,904 | 73.49% |

| 2015 | 19,988,204 | 72.91% |

| 2014 | 20,209,092 | 72.52% |

| 2013 | 20,376,677 | 72.37% |

| 2012 | 20,644,478 | 72.10% |

| 2011 | 21,010,590 | 71.95% |

| 2010 | 21,019,438 | 72.04% |

| 2009 | 20,313,594 | 72.91% |

| 2008 | 19,081,686 | 73.22% |

| 2007 | 18,258,138 | 73.94% |

| 2006 | 17,754,230 | 74.21% |

| 2005 | 17,487,475 | 74.46% |

| 2004 | 17,272,044 | 75.15% |

| 2003 | 16,911,481 | 76.04% |

| 2002 | 16,611,711 | 76.77% |

| 2001 | 15,927,987 | 76.80% |

| 2000 | 15,312,289 | 76.75% |

| 1999 | 14,849,691 | 76.61% |

| 1998 | 14,506,967 | 76.78% |

| 1997 | 14,502,334 | 77.20% |

| 1996 | 14,367,520 | 77.40% |

| 1995 | 14,261,781 | 77.78% |

| 1994 | 14,278,790 | 77.97% |

| 1993 | 14,304,803 | 78.22% |

| 1992 | 14,487,359 | 78.58% |

| 1991 | 14,358,953 | 78.76% |

| 1990 | 13,818,637 | 78.48% |

| 1989 | 13,538,560 | 78.13% |

| 1988 | 13,055,337 | 77.83% |

| 1987 | 12,766,642 | 78.12% |

| 1986 | 12,503,511 | 77.69% |

| 1985 | 12,247,055 | 77.40% |

| 1984 | 12,241,940 | 77.42% |

| 1983 | 12,464,661 | 77.68% |

| 1982 | 12,425,780 | 78.03% |

| 1981 | 12,371,672 | 77.98% |

| 1980 | 12,096,895 | 78.18% |

| 1979 | 11,569,899 | 78.11% |

| 1978 | 11,260,092 | 78.03% |

| 1977 | 11,285,787 | 78.39% |

| 1976 | 11,012,137 | 78.58% |

| 1975 | 11,184,859 | 78.99% |

| 1974 | 10,223,729 | 78.14% |

| 1973 | 9,602,123 | 77.27% |

| 1972 | 9,214,860 | 76.73% |

| 1971 | 8,948,644 | 76.04% |

| 1970 | 8,580,887 | 74.91% |

| 1965 | 5,920,864 | 67.04% |

| 1961 | 4,145,065 | 61.80% |

| 1955 | 2,653,034 | 55.65% |

| 1950 | 2,281,298 | 49.96% |

College Enrollment by Degree

College enrollment statistics indicate that, whether they earn their degree or drop out, most undergraduate students make only one attempt to complete their college education.

- 72.63% of college students at all education levels attend public institutions.

- Among the 5.09 million undergraduates who attend private institutions, 80.77% attend nonprofit schools.

- 50.01% of graduate students attend public institutions.

- 61.21% of undergraduates are full-time or full-time equivalent (FTE) students.

- An estimated 4.21 million college students graduated in 2023.

- 24.06% received associate’s degrees.

- 50.2% received bachelor’s degrees.

- 20.93% earned master’s degrees.

- 4.8% earned doctorates or professional degrees.

- 52.18% of all bachelor’s degrees are in 5 fields.

- 18.63% in business

- 13.09% in health professions and related studies.

- 7.5% in social sciences and history.

- 6.52% in biological and biomedical sciences.

- 6.43% in psychology.

- 66.82% of associates’ degrees conferred are in 3 fields.

- 38.01% are in Liberal arts and sciences, general studies, and humanities.

- 17.06% in health professions and related.

- 11.21% in business.

College Enrollment by Institution Type

Most postsecondary students attend degree-granting 4-year public institutions.

- Among new high school graduates, 16.9% enroll in 2-year colleges; 45.1% enroll in 4-year programs.

- 13.92 million or 74.93% of all college students attend 4-year institutions.

- 4.66 million or 25.07% of all students attend 2-year institutions.

- 13.49 million or 72.63% of all postsecondary students attend public institutions.

- Among the 5.08 million or 27.25% of postsecondary students who attend private institutions, 80.77% attend nonprofit schools while 19.23% attend for-profit institutions.

| Year | % Public Institution Enrollment | % Full-Time Enrollment |

|---|---|---|

| Year 2024 (Projected) | % Public Institution Enrollment 73.20% | % Full-Time Enrollment 60.80% |

| Year 2023 (Projected) | % Public Institution Enrollment 73.20% | % Full-Time Enrollment 60.80% |

| Year 2022 | % Public Institution Enrollment 72.60% | % Full-Time Enrollment 60.70% |

| Year 2021 | % Public Institution Enrollment 72.60% | % Full-Time Enrollment 60.70% |

| Year 2020 | % Public Institution Enrollment 73.00% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.00% |

| Year 2019 | % Public Institution Enrollment 73.90% | % Full-Time Enrollment 60.90% |

| Year 2018 | % Public Institution Enrollment 74.00% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.00% |

| Year 2017 | % Public Institution Enrollment 73.70% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.10% |

| Year 2016 | % Public Institution Enrollment 73.50% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.10% |

| Year 2015 | % Public Institution Enrollment 72.90% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.50% |

| Year 2014 | % Public Institution Enrollment 72.50% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.60% |

| Year 2013 | % Public Institution Enrollment 72.40% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.80% |

| Year 2012 | % Public Institution Enrollment 72.10% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.70% |

| Year 2011 | % Public Institution Enrollment 71.90% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.90% |

| Year 2010 | % Public Institution Enrollment 72.00% | % Full-Time Enrollment 62.30% |

| Year 2005 | % Public Institution Enrollment 74.50% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.70% |

| Year 2000 | % Public Institution Enrollment 76.80% | % Full-Time Enrollment 58.80% |

| Year 1995 | % Public Institution Enrollment 77.80% | % Full-Time Enrollment 57.00% |

| Year 1990 | % Public Institution Enrollment 78.50% | % Full-Time Enrollment 56.60% |

| Year 1985 | % Public Institution Enrollment 77.40% | % Full-Time Enrollment 57.80% |

| Year 1980 | % Public Institution Enrollment 78.20% | % Full-Time Enrollment 58.70% |

| Year 1975 | % Public Institution Enrollment 79.00% | % Full-Time Enrollment 61.20% |

| Year 1970 | % Public Institution Enrollment 74.90% | % Full-Time Enrollment 67.80% |

| Year 1965 | % Public Institution Enrollment 67.00% | % Full-Time Enrollment 69.20% |

| Year 1959 | % Public Institution Enrollment 59.90% | % Full-Time Enrollment 66.50% |

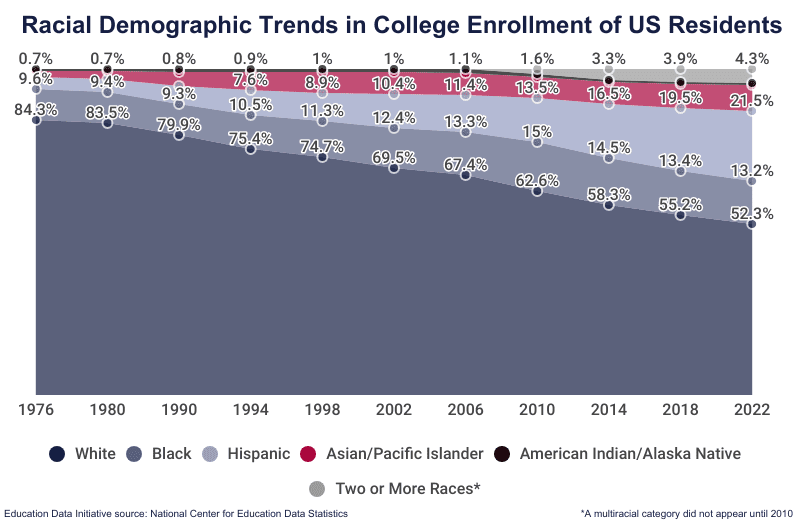

College Enrollment by Race or Ethnicity

Demographic statistics are imperfect because many people do not fit easily into just one category. Not all races are represented, and some data, especially when it is historical, use obsolete definitions and terminology. The language of this report conforms to the language used in available data sets.

- 52.3% of college students are White or Caucasian; excluding nonresident noncitizens or international students.

- 55.5% of White or Caucasian students enroll at 4-year institutions.

- As a percentage of total student enrollments, the rate of enrollment of students of color has increased from 15.36% in 1976 to 45.23% in 2022, an absolute increase of 29.87%.

- Black and African American student enrolment has seen an absolute increase of 3.5% since 1976 relative to total enrollment.

- 21.18% of postsecondary students were white males in Fall 2022.

- 18.03% of graduate students were white males in Fall 202.

- Enrollment among Hispanic females has seen an absolute increase of 10.61% from 1976 to 2022 relative to total enrollment.

- American Indians and Alaska Natives had a low absolute increase of enrollment relative to total enrollments, increasing by 0.043% since 1976.

- The absolute increase in enrollment of American Indian and Alaska Native students in graduate programs is similarly low, increasing by 0.012% since 1976.

American Indian or Alaska Native Enrollment

Postsecondary attendance among American Indian or Alaska Native students was in decline between 2012 and 2021.

- 0.65% of students identify as American Indian or Alaska Native.

- Attendance among students of this demographic has increased 56.1% relative to 1976.

- American Indian or Alaska Native students saw their highest rate of attendance in 2007 (1.08%).

- 77.37% of students in this demographic attend public institutions.

- 64.74% of American Indian or Alaska Native students attend 4-year institutions.

Asian or Asian American Enrollment

Postsecondary attendance among Asian or Asian American students has steadily grown since 2010; attendance rates prior to 2010 combine Asian and Pacific Islander student populations.

- 7.38% of students identify as Asian or Asian American.

- Attendance among students of this demographic has increased 12.6% relative to 2010.

- 74.3% of Asians or Asian American attend public institutions.

- 78.77% of Asian or Asian American students attend 4-year institutions.

Black or African-American Enrollment

Postsecondary attendance among Black or African American students was on the rise until 2010; since then, it has been in decline.

- 12.5% of students identify as Black or African American.

- Attendance among students of this demographic has increased by 124.9% relative to 1976.

- 67.58% of students in this demographic attend public institutions.

- 71.88% of Black or African American students attend 4-year institutions.

Hispanic or Latino Enrollment

Postsecondary attendance among Hispanic or Latino students has skyrocketed in the last 50 years and continues to grow annually.

- 20.34% of the college student population identifies as Hispanic or Latino.

- Attendance among this demographic has increased by 884% relative to 1976.

- 80.4% of students in this demographic attend public institutions.

- 66.1% of Hispanic or Latino students enroll in 4-year colleges.

Pacific Islander Enrollment

As with the Asian or Asian American category, attendance rates prior to 2010 combined Asian and Pacific Islander student populations.

- 0.24% of the college student population identifies as Pacific Islander.

- Attendance among this demographic has declined by 30.6% relative to 2010.

- 62.8% of students in this demographic attend public institutions.

- 70.3% of Pacific Islander students enrolled in 4-year colleges.

Multiracial Enrollment

Students who identify as two or more races are categorized as multiracial. Data prior to 2010 is unavailable.

- 4.12% of the college student population identifies as multiracial.

- Attendance among multiracial students has increased by 135% relative to 2010.

- 74.3% of students in this demographic attend public institutions.

- 74.8% of multiracial students enroll in 4-year colleges.

| Year | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment | % Black or African American Enrollment |

|---|---|---|

| Year 2022 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 45.23% | % Black or African American Enrollment 12.50% |

| Year 2021 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 44.35% | % Black or African American Enrollment 12.48% |

| Year 2020 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 43.94% | % Black or African American Enrollment 12.54% |

| Year 2019 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 43.41% | % Black or African American Enrollment 12.57% |

| Year 2018 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 42.52% | % Black or African American Enrollment 12.70% |

| Year 2017 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 41.77% | % Black or African American Enrollment 12.89% |

| Year 2016 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 40.97% | % Black or African American Enrollment 13.05% |

| Year 2015 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 40.36% | % Black or African American Enrollment 13.41% |

| Year 2014 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 39.84% | % Black or African American Enrollment 13.82% |

| Year 2010 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 36.11% | % Black or African American Enrollment 14.46% |

| Year 2000 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 28.22% | % Black or African American Enrollment 11.30% |

| Year 1990 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 19.57% | % Black or African American Enrollment 9.02% |

| Year 1980 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 16.11% | % Black or African American Enrollment 9.15% |

| Year 1976 | % Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 15.35% | % Black or African American Enrollment 9.38% |

US Nonresident Enrollment

The phrase US nonresident is defined as “A person who is not a citizen or national of the United States and who is in the United States on a visa or temporary basis and does not have the right to remain indefinitely”.

- 5.2% of enrolled college students are nonresident non-citizens.

- The attendance rate among these students increased 9.3% YoY.

- Attendance among these students has increased by 342.6% relative to 1976.

- Since 2010, attendance is up 36.8%.

- 58.4% of students in this demographic attend public institutions.

- 94.2% of nonresident, non-citizen students enroll in 4-year colleges.

| Year | % Female Enrollment | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment |

|---|---|---|

| Year 2022 | % Female Enrollment 57.94% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 27.19% |

| Year 2021 | % Female Enrollment 58.37% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 26.91% |

| Year 2020 | % Female Enrollment 58.56% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 26.80% |

| Year 2019 | % Female Enrollment 57.39% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 25.89% |

| Year 2018 | % Female Enrollment 57.03% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 25.21% |

| Year 2017 | % Female Enrollment 56.66% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 24.64% |

| Year 2016 | % Female Enrollment 56.47% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 24.11% |

| Year 2015 | % Female Enrollment 56.36% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 23.71% |

| Year 2014 | % Female Enrollment 56.47% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 23.45% |

| Year 2010 | % Female Enrollment 56.96% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 21.55% |

| Year 2000 | % Female Enrollment 56.10% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 16.53% |

| Year 1990 | % Female Enrollment 54.28% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 11.06% |

| Year 1980 | % Female Enrollment 51.44% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 8.80% |

| Year 1976 | % Female Enrollment 47.23% | % Female Racial or Ethnic Minority Enrollment 7.85% |

College Enrollment by Sex or Gender

Limited data makes no significant representation of genders beyond the standard binary. Updates to data collection policies may make these statistics available in the future.

- 64.8% of American women aged 25 years and older have pursued higher education.

- 50.24% of women 25 and older have at least one degree.

- 60.51% of men aged 25 years and older have pursued higher education.

- 45.89% of men 25 and older have at least one degree.

- Women over the age of 25 are 20.15% more likely to enroll in higher education than men and 19.1% more likely to earn a degree.

- 74.3% of male college students attend public institutions; 25.7% attend private schools.

- 71.4% of female students attend public institutions; 28.6% attend private schools.

- Women are 525% more likely to attend public institutions.

- 42.7% of undergraduate students are male.

- 40% of graduate students are men.

- In 1970, 41.2% of college students were women.

- 34.2% of American males aged 18 to 24 years are enrolled in college or graduate school.

- 43.8% of American females aged 18 to 24 years are enrolled in college or graduate school.

- Among first-time, full-time bachelor’s degree-seekers, females are 32.3% more likely to complete their degree at the first institution they enrolled in and within six (6) years compared to men.

- 58.5% of bachelor’s degrees are conferred to females.

- 62.6% of associate degrees and 62.8% of master’s degrees are conferred to women, respectively.

- 57% of doctorate degrees conferred belong to women.

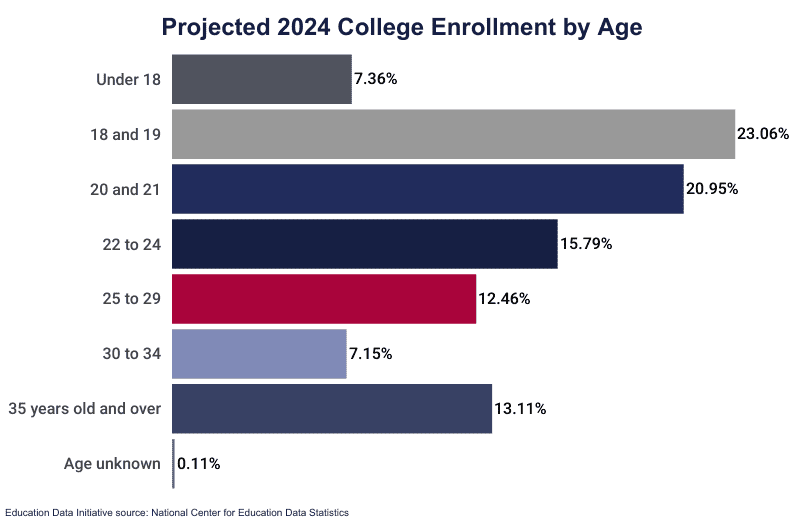

College Enrollment by Age

Most college students first enroll in their late teens as full-time students. Part-time students are more likely to be older.

- Among Americans aged 25 years and older, 37.7% have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

- 67.2% of college students are projected to be aged 24 years and under in 2024.

- 39% of American 18- to 24-year-olds are enrolled in college or graduate school.

- 74.5% of all 18- and 19-year-olds are enrolled in schools of any type.

- 30.0% of 20- to 24-year-olds are enrolled in school.

- 6.95% of Americans aged 25 to 29 years are enrolled.

- 4.19% of 30- to 34-year-olds are enrolled in postsecondary education.

- 2.83% of 35- to 39-year-olds are enrolled.

- 1.69% of 40- to 49-year-olds are enrolled.

- Among people aged 50 to 64, 0.54% are enrolled.

- 0.10% of people aged 65 years and older are enrolled in postsecondary education.

- Students enrolled in Fall 2022 were 10.5% more likely to be between the ages of 18 and 24 than students enrolled in Fall 2005.

- Among all postsecondary students, the rate of 30- to 64-year-old enrollees declined by 29.6% between 2005 and 2022.

Percentage of High School Graduates That Go to College

The percentage of high school graduates (referred to sometimes as completers) who enroll in either 2-year or 4-year institutions following graduation is referred to as the “immediate college enrollment rate”.

- In Spring 2022, 2.99 million students graduated from high school, a 7% decline relative to the Class of 2018 (the largest graduating class).

- 62% of the Class of 2022 enrolled in postsecondary institutions in Fall 2023.

- Among the Class of 2022, 16.9% enrolled in 2-year institutions in Fall 2023.

- 45.1% of the Class of 2022 enrolled in 4-year institutions.

- Among males who graduated high school in 2022, 57.2% immediately enrolled in college.

- Females in the Class of 2022 had a 66% immediate matriculation rate.

- Among the Class of 2022, female students were 94.1% more likely to immediately matriculate.

- 2022 female high school graduates were 65% more likely to immediately enroll in 4-year institutions compared to graduating males.

- Among immediately college-bound members of the Class of 2021, female students were 86.4% more likely to attend 4-year institutions compared to males.

State College Enrollment Statistics

College enrollment statistics indicate that many students are willing to travel out of their home state for their college education.

- California has the highest number of enrolled college students at 2.487 million, a 97.8% increase relative to 1970.

- New York and Texas are the only other states with more than a million college students enrolled.

- Alaska has the smallest student population with 22,152 students enrolled; that’s a 112.7% increase relative to 1970.

- Wyoming, Montana, and Vermont all have fewer than 50,000 enrolled college students.

- New Hampshire, Utah, and Idaho have seen the largest increases in enrollment rates relative to 2010 at 184.01%, 56.94%, and 47% respectively.

- 45 states have seen a decline in postsecondary enrollment since 2010.

- Iowa and Alaska saw the largest declines in enrollment since 2010, losing 47% and 42.1% of their respective student populations

- The only jurisdictions to see an increase in the number of students enrolled since 2010 are New Hampshire, Utah, Idaho, Delaware, and Texas, as well as the District of Columbia.

- New Hampshire and Utah had the largest YoY student population growth at 8.1% and 2.87%, respectively.

| State | College Enrollment | % Change, 2010 to 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| State Alabama | College Enrollment 294,009 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -10.30% |

| State Alaska | College Enrollment 20,152 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -42.10% |

| State Arizona | College Enrollment 624,719 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -21.30% |

| State Arkansas | College Enrollment 154,781 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.00% |

| State California | College Enrollment 2,486,788 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -8.40% |

| State Colorado | College Enrollment 346,716 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -6.20% |

| State Connecticut | College Enrollment 187,764 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -5.80% |

| State Delaware | College Enrollment 57,022 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 3.20% |

| State District of Columbia | College Enrollment 99,329 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 8.00% |

| State Florida | College Enrollment 999,223 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -11.20% |

| State Georgia | College Enrollment 541,594 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -4.80% |

| State Hawaii | College Enrollment 58,841 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -24.60% |

| State Idaho | College Enrollment 125,249 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 47.00% |

| State Illinois | College Enrollment 677,446 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -25.30% |

| State Indiana | College Enrollment 436,234 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -5.10% |

| State Iowa | College Enrollment 202,287 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -47.00% |

| State Kansas | College Enrollment 185,985 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -13.40% |

| State Kentucky | College Enrollment 261,751 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -10.10% |

| State Louisiana | College Enrollment 238,689 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -9.50% |

| State Maine | College Enrollment 71,475 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -1.30% |

| State Maryland | College Enrollment 329,092 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.90% |

| State Massachusetts | College Enrollment 468,960 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -7.60% |

| State Michigan | College Enrollment 466,458 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -33.10% |

| State Minnesota | College Enrollment 373,128 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -19.80% |

| State Mississippi | College Enrollment 155,950 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -13.40% |

| State Missouri | College Enrollment 333,470 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -25.00% |

| State Montana | College Enrollment 47,134 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -11.50% |

| State Nebraska | College Enrollment 134,815 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -6.80% |

| State Nevada | College Enrollment 113,588 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.20% |

| State New Hampshire | College Enrollment 214,537 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 184.00% |

| State New Jersey | College Enrollment 378,819 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -14.70% |

| State New Mexico | College Enrollment 110,082 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -32.30% |

| State New York | College Enrollment 1,117,623 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -14.40% |

| State North Carolina | College Enrollment 553,180 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -5.60% |

| State North Dakota | College Enrollment 51,074 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -10.20% |

| State Ohio | College Enrollment 612,352 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -17.80% |

| State Oklahoma | College Enrollment 184,218 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -20.10% |

| State Oregon | College Enrollment 194,987 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -22.50% |

| State Pennsylvania | College Enrollment 633,991 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -21.20% |

| State Rhode Island | College Enrollment 74,413 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.60% |

| State South Carolina | College Enrollment 242,672 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -5.60% |

| State South Dakota | College Enrollment 51,317 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.10% |

| State Tennessee | College Enrollment 308,710 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.20% |

| State Texas | College Enrollment 1,567,017 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 2.00% |

| State Utah | College Enrollment 401,218 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 56.90% |

| State Vermont | College Enrollment 39,888 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.50% |

| State Virginia | College Enrollment 546,280 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -5.50% |

| State Washington | College Enrollment 311,068 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -19.90% |

| State West Virginia | College Enrollment 132,923 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -12.80% |

| State Wisconsin | College Enrollment 316,129 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -17.70% |

| State Wyoming | College Enrollment 29,971 | % Change, 2010 to 2020 -21.70% |

College Enrollment in Alabama

Among students enrolled full-time in Alabama postsecondary institutions, 68.3% are state residents and 31.7% are nonresidents.

- 294,009 students are enrolled in Alabama colleges.

- Enrollment in Alabama has declined by 10.8% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment in Alabama increased by 215.2%.

- 57.9% of full-time students in Alabama are female.

- 86.1% of students enrolled in Alabama postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Alabama residents enrolled in college, 14.6% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Alaska

Among students enrolled full-time in Alaska postsecondary institutions, 86.7% are state residents and 13.3% are nonresidents.

- 20,152 students are enrolled in Alaska colleges.

- Enrollment in Alaska has declined 42.1% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 267.4%.

- 57.2% of full-time students in Alaska are female.

- 95.1% of students enrolled in Alaska postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Alaska residents enrolled in college, 51.3% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Arizona

Among students enrolled full-time in Arizona postsecondary institutions, 60.3% are state residents and 39.7% are nonresidents.

- 624,719 students are enrolled in Arizona colleges.

- Enrollment in Arizona has declined 21.3% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 624.2%.

- 60.4% of full-time students in Arizona are female.

- 60.2% of students enrolled in Arizona postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Arizona residents enrolled in college, 14.7% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Arkansas

Among students enrolled full-time in Arkansas postsecondary institutions, 68.3% are state residents and 31.7% are nonresidents.

- 154,781 students are enrolled in Arkansas colleges.

- Enrollment in Arkansas has declined by 12% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 237.9%.

- 58.6% of full-time students in Arkansas are female.

- 89.5% of students enrolled in Arkansas postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Arkansas residents enrolled in college, 17.3% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in California

Among students enrolled full-time in California postsecondary institutions, 88.8% are state residents and 112% are nonresidents.

- 2,486,788 students are enrolled in California colleges.

- Enrollment in California has declined by 8.4% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 115.9%.

- 57.3% of full-time students in California are female.

- 81.7% of students enrolled in California postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all California residents enrolled in college, 12.5% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Colorado

Among students enrolled full-time in Colorado postsecondary institutions, 66.3% are state residents and 33.7% are nonresidents.

- 346,716 students are enrolled in Colorado colleges.

- Enrollment in Colorado has declined by 6.2% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 199.4%.

- 56.1% of full-time students in Colorado are female.

- 77.6% of students enrolled in Colorado postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Colorado residents enrolled in college, 31.8% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Connecticut

Among students enrolled full-time in Connecticut postsecondary institutions, 61.4% are state residents and 38.6% are nonresidents.

- 187,764 students are enrolled in Connecticut colleges.

- Enrollment in Connecticut has declined by 5.8% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 59.9%.

- 57.2% of full-time students in Connecticut are female.

- 51.3% of students enrolled in Connecticut postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Connecticut residents enrolled in college, 43.5% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Delaware

Among students enrolled full-time in Delaware postsecondary institutions, 50.5% are state residents and 49.5% are nonresidents.

- 57,022 students are enrolled in Delaware colleges.

- Enrollment in Delaware has increased by 3.2% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 118.8%.

- 59.4% of full-time students in Delaware are female.

- 72.9% of students enrolled in Delaware postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Delaware residents enrolled in college, 27.1% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in the District of Columbia

Among students enrolled full-time in D.C. postsecondary institutions, 6.9% are D.C. residents and 93.1% are nonresidents.

- 99,329 students are enrolled in D.C. colleges.

- Enrollment in D.C. has increased by 8% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 19.2%.

- 62.1% of full-time students in D.C. are female.

- 3.6% of students enrolled in D.C. postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all D.C. residents enrolled in college, 78.1% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Florida

Among students enrolled full-time in Florida postsecondary institutions, 79.4% are state residents and 20.6% are nonresidents.

- 999,223 students are enrolled in Florida colleges.

- Enrollment in Florida has declined by 11.2% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 377.6%.

- 57.3% of full-time students in Florida are female.

- 73.6% of students enrolled in Florida postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Florida residents enrolled in college, 15.2% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Georgia

Among students enrolled full-time in Georgia postsecondary institutions, 79.9% are state residents and 20.1% are nonresidents.

- 541,594 students are enrolled in Georgia colleges.

- Enrollment in Georgia has declined by 4.8% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 349.7%.

- 59% of full-time students in Georgia are female.

- 80.5% of students enrolled in Georgia postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Georgia residents enrolled in college, 23.8% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Hawaii

Among students enrolled full-time in Hawaii postsecondary institutions, 66.7% are state residents and 33.3% are nonresidents.

- 58,841 students are enrolled in Hawaii colleges.

- Enrollment in Hawaii has declined by 24.6% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 113.5%.

- 62.8% of full-time students in Hawaii are female.

- 82.2% of students enrolled in Hawaii postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Hawaii residents enrolled in college, 42.4% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Idaho

Among students enrolled full-time in Idaho postsecondary institutions, 60.3% are state residents and 39.7% are nonresidents.

- 125,249 students are enrolled in Idaho colleges.

- Enrollment in Idaho has increased 47% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 146.5%.

- 55.4% of full-time students in Idaho are female.

- 62.5% of students enrolled in Idaho postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Idaho residents enrolled in college, 28.7% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Illinois

Among students enrolled full-time in Illinois postsecondary institutions, 79.9% are state residents and 20.1% are nonresidents.

- 677,446 students are enrolled in Illinois colleges.

- Enrollment in Illinois has declined 25.4% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 100.6%.

- 55.6% of full-time students in Illinois are female.

- 61.6% of students enrolled in Illinois postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Illinois residents enrolled in college, 32.9% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Indiana

Among students enrolled full-time in Indiana postsecondary institutions, 67.2% are state residents and 32.8% are nonresidents.

- 436,234 students are enrolled in Indiana colleges.

- Enrollment in Indiana has declined by 5.1% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 138.5%.

- 54.6% of full-time students in Indiana are female.

- 80.0% of students enrolled in Indiana postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Indiana residents enrolled in college, 16.3% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Iowa

Among students enrolled full-time in Iowa postsecondary institutions, 64.3% are state residents and 35.7% are nonresidents.

- 202,287 students are enrolled in Iowa colleges.

- Enrollment in Iowa has declined 47% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 250.7%.

- 52% of full-time students in Iowa are female.

- 74.6% of students enrolled in Iowa postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Iowa residents enrolled in college, 15.2% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Kansas

Among students enrolled full-time in Kansas postsecondary institutions, 69.4% are state residents and 30.6% are nonresidents.

- 185,985 students are enrolled in Kansas colleges.

- Enrollment in Kansas has declined by 13.4% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 109.6%.

- 53% of full-time students in Kansas are female.

- 87.7% of students enrolled in Kansas postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Kansas residents enrolled in college, 19.4% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Kentucky

Among students enrolled full-time in Kentucky postsecondary institutions, 77% are state residents and 23% are nonresidents.

- 261,751 students are enrolled in Kentucky colleges.

- Enrollment in Kentucky has declined by 10.1% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 195.3%.

- 59.7% of full-time students in Kentucky are female.

- 74.2% of students enrolled in Kentucky postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Kentucky residents enrolled in college, 16.7% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Louisiana

Among students enrolled full-time in Louisiana postsecondary institutions, 79.1% are state residents and 20.9% are nonresidents.

- 238,689 students are enrolled in Louisiana colleges.

- Enrollment in Louisiana has declined 9.5% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 118.4%.

- 60.6% of full-time students in Louisiana are female.

- 86.8% of students enrolled in Louisiana postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Louisiana residents enrolled in college, 15.9% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Maine

Among students enrolled full-time in Maine postsecondary institutions, 61.7% are state residents and 38.3% are nonresidents.

- 71,475 students are enrolled in Maine colleges.

- Enrollment in Maine has declined by 1.3% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 112.1%.

- 57.9% of full-time students in Maine are female.

- 65.5% of students enrolled in Maine postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Maine residents enrolled in college, 28.4% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Maryland

Among students enrolled full-time in Maryland postsecondary institutions, 77.3% are state residents and 22.7% are nonresidents.

- 329,092 students are enrolled in Maryland colleges.

- Enrollment in Maryland has declined by 12.9% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 152.6%.

- 55.4% of full-time students in Maryland are female.

- 81.7% of students enrolled in Maryland postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Maryland residents enrolled in college, 36.6% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Massachusetts

Among students enrolled full-time in Massachusetts postsecondary institutions, 55.7% are state residents and 44.3% are nonresidents.

- 468,960 students are enrolled in Massachusetts colleges.

- Enrollment in Massachusetts has declined by 7.6% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 67.1%.

- 55.8% of full-time students in Massachusetts are female.

- 38.3% of students enrolled in Massachusetts postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Massachusetts residents enrolled in college, 37.7% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Michigan

Among students enrolled full-time in Michigan postsecondary institutions, 83.5% are state residents and 16.5% are nonresidents.

- 466,458 students are enrolled in Michigan colleges.

- Enrollment in Michigan has declined 33.1% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 77.7%.

- 55% of full-time students in Michigan are female.

- 87.1% of students enrolled in Michigan postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Michigan residents enrolled in college, 14% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Minnesota

Among students enrolled full-time in Minnesota postsecondary institutions, 77.9% are state residents and 22.1% are nonresidents.

- 373,128 students are enrolled in Minnesota colleges.

- Enrollment in Minnesota has declined by 19.8% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 189.5%.

- 59.7% of full-time students in Minnesota are female.

- 59.8% of students enrolled in Minnesota postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Minnesota residents enrolled in college, 34.7% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Mississippi

Among students enrolled full-time in Mississippi postsecondary institutions, 72.5% are state residents and 27.5% are nonresidents.

- 155,950 students are enrolled in Mississippi colleges.

- Enrollment in Mississippi has declined by 13.4% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 143.3%.

- 60.1% of full-time students in Mississippi are female.

- 89% of students enrolled in Mississippi postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Mississippi residents enrolled in college, 13% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Missouri

Among students enrolled full-time in Missouri postsecondary institutions, 75% are state residents and 25% are nonresidents.

- 333,470 students are enrolled in Missouri colleges.

- Enrollment in Missouri has declined by 25.0% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 141.8%.

- 56.2% of full-time students in Missouri are female.

- 63.1% of students enrolled in Missouri postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Missouri residents enrolled in college, 23.9% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Montana

Among students enrolled full-time in Montana postsecondary institutions, 54.6% are state residents and 45.4% are nonresidents.

- 47,134 students are enrolled in Montana colleges.

- Enrollment in Montana has declined by 11.5% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 77.2%.

- 53% of full-time students in Montana are female.

- 92.4% of students enrolled in Montana postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Montana residents enrolled in college, 28.6% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Nebraska

Among students enrolled full-time in Nebraska postsecondary institutions, 74% are state residents and 26% are nonresidents.

- 134,815 students are enrolled in Nebraska colleges.

- Enrollment in Nebraska has declined by 6.8% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 116.2%.

- 55.7% of full-time students in Nebraska are female.

- 72.8% of students enrolled in Nebraska postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Nebraska residents enrolled in college, 24.9% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in Nevada

Among students enrolled full-time in Nevada postsecondary institutions, 89.5% are state residents and 10.5% are nonresidents.

- 113,588 students are enrolled in Nevada colleges.

- Enrollment in Nevada has declined by 12.2% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 846.4%.

- 59.4% of full-time students in Nevada are female.

- 91.7% of students enrolled in Nevada postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all Nevada residents enrolled in college, 26% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in New Hampshire

Among students enrolled full-time in New Hampshire postsecondary institutions, 21.4% are state residents and 78.6% are nonresidents.

- 214,537 students are enrolled in New Hampshire colleges.

- Enrollment in New Hampshire has increased 184% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 156.9%.

- 58.6% of full-time students in New Hampshire are female.

- 15.1% of students enrolled in New Hampshire postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all New Hampshire residents enrolled in college, 50.1% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in New Jersey

Among students enrolled full-time in New Jersey postsecondary institutions, 88.7% are state residents and 11.3% are nonresidents.

- 378,819 students are enrolled in New Jersey colleges.

- Enrollment in New Jersey has declined 14.7% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 105.5%.

- 52.8% of full-time students in New Jersey are female.

- 77.9% of students enrolled in New Jersey postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all New Jersey residents enrolled in college, 39.2% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in New Mexico

Among students enrolled full-time in New Mexico postsecondary institutions, 82.7% are state residents and 17.3% are nonresidents.

- 110,082 students are enrolled in New Mexico colleges.

- Enrollment in New Mexico has declined by 32.3% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased by 265.6%.

- 59.2% of full-time students in New Mexico are female.

- 96.4% of students enrolled in New Mexico postsecondary institutions attend public schools.

- Among all New Mexico residents enrolled in college, 18.7% leave the state to attend school.

College Enrollment in New York

Among students enrolled full-time in New York postsecondary institutions, 73.9% are state residents and 26.1% are nonresidents.

- 1,117,623 students are enrolled in New York colleges.

- Enrollment in New York has declined by 14.4% since 2010.

- Between 1970 and 2010, enrollment increased 61.8%.

- 56.4% of full-time students in New York are female.