A Quiet Hero of Iwo Jima: Major Robert Hugo Dunlap's Extraordinary Legacy

|

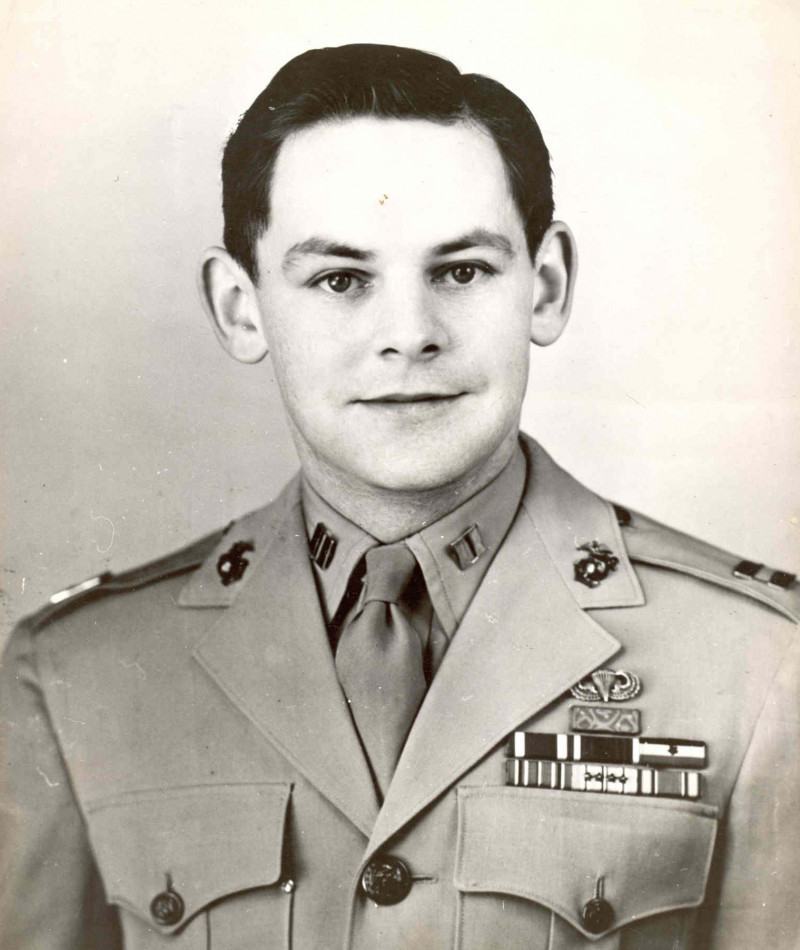

Major Robert Hugo Dunlap |

A Quiet Hero from Abingdon: Major Robert Hugo Dunlap's Extraordinary Legacy

A small-town Illinois Marine who embodied the highest traditions of American military service. John Wayne wanted to play him, but he refused.

In the vast tapestry of American military heroism, some stories shine with such luminous distinction that they transcend the ordinary bounds of courage. The tale of Robert Hugo Dunlap—a diminutive Marine from rural Illinois who became one of the most decorated heroes of World War II—is one such story that continues to inspire nearly eight decades after his extraordinary actions on the blood-soaked volcanic island of Iwo Jima.

The Making of a Marine

Born on October 19, 1920, in the farming community of Abingdon, Illinois, Robert Hugo Dunlap seemed an unlikely candidate for military glory. Standing just five feet six inches tall and weighing a mere 148 pounds, he hardly fit the barrel-chested stereotype of the recruiting poster Marine. Yet beneath his unassuming exterior burned the kind of quiet determination that would later distinguish him in the crucible of combat.

Dunlap's formative years in Abingdon painted the portrait of a well-rounded young American. An active high school student, he excelled in football and basketball despite his small stature, ran track, and even participated in class theatrical productions. These diverse pursuits revealed a young man comfortable with both athletic competition and public performance—qualities that would serve him well in the demanding role of military leadership.

At Monmouth College in nearby Monmouth, Illinois, Dunlap continued to defy expectations based on his physical size. He became a prominent football player and trackman, eventually serving as treasurer of the student body in his senior year. His academic focus on economics and business administration, with a minor in mathematics, suggested a young man preparing for a conventional post-war career in commerce or education.

The attack on Pearl Harbor, however, altered the trajectory of countless American lives, including Dunlap's. On March 5, 1942, while still completing his studies, the 21-year-old enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve. He graduated from Monmouth College in May 1942 with his Bachelor of Arts degree, then immediately reported for active duty, commissioned as a second lieutenant on July 18, 1942.

The Paratrooper's Path

Dunlap's early Marine Corps career reflected his appetite for challenge and excellence. Volunteering for parachute training, he was sent to the specialized school at Camp Gillespie in San Diego, California. On November 23, 1942, he earned his jump wings and was assigned to the elite 3rd Parachute Battalion. The Marine paratroopers, though ultimately disbanded as a separate force, represented the cutting edge of amphibious warfare doctrine—a fitting assignment for a young officer destined for distinction.

The Solomon Islands campaign of 1943 provided Dunlap's first taste of combat leadership. Promoted to first lieutenant in April 1943, he participated in the invasions of Vella Lavella and Bougainville. It was during the brutal Bougainville fighting that Dunlap first demonstrated the exceptional courage that would define his military career.

On December 9, 1943, Lieutenant Dunlap's rifle platoon found itself pinned down by devastating Japanese machine gun fire. With his men trapped and casualties mounting, the young platoon leader made a decision that would become his signature: he exposed himself to the withering enemy fire to rally his depleted unit. Through personal example and tactical skill, he maneuvered his Marines into position to retake lost ground. For this action, Admiral William "Bull" Halsey awarded him a Letter of Commendation, later upgraded to the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal.

Preparing for the Ultimate Test

Following the Solomon Islands campaign, First Lieutenant Dunlap returned to the United States in March 1944 to join the newly formed 5th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton, California. The dissolution of the parachute battalions had necessitated reassignment, and Dunlap initially served as a machine gun platoon leader in Company G, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines.

His proven leadership abilities soon earned recognition. When the division deployed for its second Pacific tour in the summer of 1944, Dunlap was promoted to captain on October 2, 1944, and given command of Company C, 1st Battalion, 26th Marines. This rifle company command would prove to be his destiny, placing him at the forefront of what would become the bloodiest battle in Marine Corps history.

The Furnace of Iwo Jima

By February 1945, the American advance across the Pacific had reached Japan's doorstep. The strategic island of Iwo Jima, just 660 miles from Tokyo, represented both a crucial stepping stone for the planned invasion of Japan and a heavily fortified obstacle defended by 22,000 Japanese troops under General Tadamichi Kuribayashi.

Unlike previous Pacific battles where the Japanese had concentrated their defenses on the beaches, Kuribayashi had prepared an intricate network of tunnels, caves, and fortified positions designed to bleed the Americans white. The volcanic island's eight square miles contained over eleven miles of interconnected underground passages, creating a defensive maze that would test American resolve to its limits.

On February 19, 1945, the largest Pacific amphibious assault force in Marine Corps history—70,000 Marines and sailors—began landing on Iwo Jima's black volcanic beaches. Captain Dunlap's Company C was among the first waves, and from the moment they stepped ashore, they faced a hell of artillery, mortar, rifle, and machine gun fire that seemed to pour from every direction.

Two Days That Defined a Hero

The actions that would earn Captain Robert Hugo Dunlap the Medal of Honor took place on February 20-21, 1945, during some of the most savage fighting of the Pacific war. As Company C advanced from the low ground toward the steep cliffs dominating the landscape, they encountered the kind of withering fire that had already begun to earn Iwo Jima its grim reputation as "the graveyard of the Pacific."

The Japanese had positioned their weapons in caves and fortified positions high on the cliffs, creating interlocking fields of fire that turned every advance into a deadly gauntlet. When the volume of enemy fire became so intense that his company's progress ground to a halt, Captain Dunlap made a decision that exemplified both tactical brilliance and extraordinary personal courage.

Rather than accept the stalemate, Dunlap crawled alone approximately 200 yards forward of his front lines while his Marines watched in a mixture of fear and admiration. Under constant fire, he positioned himself at the base of the cliff, just 50 yards from Japanese positions, and conducted a careful reconnaissance of enemy gun emplacements. This intelligence-gathering mission, conducted in full view of the enemy and under direct fire, provided crucial tactical information that would prove decisive.

Returning to his lines, Dunlap immediately relayed the vital intelligence to supporting artillery and naval gunfire units. But his heroism was far from complete. Recognizing that accurate fire direction required continuous observation, he again exposed himself to enemy fire by positioning himself at an exposed vantage point where he could effectively coordinate the bombardment of Japanese positions.

For two days and two nights, without respite and under constant enemy fire, Captain Dunlap maintained his exposed position, skillfully directing what his Medal of Honor citation would describe as "a smashing bombardment against the almost impregnable Japanese positions." Despite heavy Marine casualties and numerous obstacles, his cool decision-making, indomitable fighting spirit, and daring tactics proved instrumental in breaking the Japanese defensive line in his sector.

The Price of Valor

On February 26, 1945, Captain Dunlap's extraordinary run of combat leadership came to an abrupt end when he was felled by a bullet wound to his left hip. The injury, though not immediately life-threatening, required his evacuation from Iwo Jima and began a lengthy period of hospitalization that would extend for nearly fourteen months.

Dunlap's medical odyssey took him through a succession of naval hospitals: first to Guam for initial treatment, then to Pearl Harbor, San Francisco, and finally to Great Lakes Naval Hospital in Illinois. The extended hospitalization reflected both the severity of his wound and the limited medical technology of the era, but it also provided time for reflection on his extraordinary service.

Recognition and Return

On December 18, 1945, just days after marrying his college sweetheart, Mary Louise Frantz, Captain Dunlap stood in the White House East Room as President Harry S. Truman placed the Medal of Honor around his neck. The ceremony honored six service members who had demonstrated exceptional valor during the war, but Dunlap's citation stood out for its detailed description of sustained heroism over multiple days.

The official citation captured the essence of his actions: "For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty... A brilliant leader, Captain Dunlap inspired his men to heroic efforts during this critical phase of the battle and by his cool decision, indomitable fighting spirit, and daring tactics in the face of fanatic opposition greatly accelerated the final decisive defeat of Japanese countermeasures in his sector."

Captain Dunlap was one of 27 Marines and sailors who earned the Medal of Honor for actions on Iwo Jima—more than any other single battle in American military history. This extraordinary concentration of heroism reflected the savage nature of the fighting, where exceptional courage became routine and where men like Dunlap repeatedly risked their lives for their comrades and their mission.

Following his discharge from Great Lakes Naval Hospital on April 20, 1946, Major Dunlap (he had been promoted during his hospitalization) went on inactive duty in September 1946 and was officially retired with the rank of major on December 1, 1946. His formal military career had lasted just over four years, but those years had encompassed some of the most intense combat of World War II.

The Civilian Years

The transition from war hero to civilian life is never simple, and for Major Dunlap, the post-war years brought both challenges and opportunities. Returning to his beloved Abingdon, he initially embraced the agricultural life that had sustained his family for generations. For approximately eighteen years, he worked as a farmer, finding solace in the cyclical rhythms of planting and harvest that contrasted sharply with the violent chaos of his war years.

But Dunlap's intellectual gifts and natural leadership abilities eventually drew him into education. In the 1960s, he became a schoolteacher, dedicating himself to shaping young minds with the same quiet determination that had characterized his military service. His educational career continued until his retirement in 1982, spanning more than two decades of service to his community's children.

Throughout his civilian years, Dunlap maintained a characteristic humility about his wartime service. In 1949, when Hollywood legend John Wayne contacted him on behalf of Paramount Pictures to inquire about purchasing the film rights to his story, Dunlap declined. His concern that the film would present an idealized portrait of the war reflected his deep understanding of combat's harsh realities and his reluctance to glamorize experiences that had cost so many lives.

Family Legacy and Honors

Dunlap's family connections to military service extended far beyond his own extraordinary record. His cousin, Navy Vice Admiral James Bond Stockdale, who grew up alongside him in Abingdon, would earn his own Medal of Honor for actions during the Vietnam War, making theirs a family distinguished by the highest levels of military valor across multiple generations. Both men were members of the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, connecting their service to the broader tradition of American military sacrifice.

The small town of Abingdon took pride in producing two Medal of Honor recipients, and in 2014, a veterans memorial was dedicated to honor both Dunlap and Stockdale. This memorial serves as a permanent reminder of how a small Illinois farming community contributed extraordinary leaders to American military history.

The Weapons of War and Memory

Among the most tangible connections to Dunlap's wartime service is the M1941 Johnson rifle he carried during the Iwo Jima campaign. Serial number A0009, this semiautomatic rifle represented cutting-edge military technology for its time and became a treasured piece of family history. Dunlap kept the weapon throughout his life, displaying it in his home as a reminder of his service and sacrifice.

Following Dunlap's death, the rifle found a permanent home at Simpson Ltd, Firearms for Collectors, in Galesburg, Illinois, where it remains on public display. This placement ensures that future generations can view an actual artifact from one of the most significant battles of World War II, carried by one of the war's most decorated heroes.

Recent Research and Continuing Recognition

Contemporary military historians continue to study Dunlap's actions at Iwo Jima as an example of exceptional small-unit leadership under extreme conditions. The National World War II Museum in New Orleans has featured his story in educational materials, highlighting how individual courage can influence the outcome of major military operations.

The Marine Corps University's History Division maintains comprehensive records of Dunlap's service, including his Medal of Honor citation, photographs, and biographical information. These materials serve both as historical resources and as inspirational examples for current and future Marines studying the principles of leadership and courage under fire.

Modern military leadership courses frequently reference Dunlap's actions as a case study in tactical decision-making and personal courage. His willingness to personally conduct reconnaissance under fire, combined with his ability to effectively coordinate supporting fires while exposed to enemy action, exemplifies the kind of battlefield leadership that military academies strive to instill in their graduates.

The Measure of a Life

Major Robert Hugo Dunlap passed away on March 24, 2000, at the age of 79, in Monmouth, Illinois. He was laid to rest in Warren County Memorial Park in Monmouth, surrounded by the Illinois prairie he had loved throughout his life. His funeral drew hundreds of mourners, including fellow veterans, former students, and community members whose lives he had touched during his long civilian career.

His daughter, Donna Butler, has preserved her father's memory through interviews and public statements that reveal the man behind the medal. According to Butler, her father rarely spoke of his wartime experiences, preferring to focus on his post-war contributions to education and community service. This humility, she noted, was characteristic of his generation of veterans who viewed their wartime service as duty rather than grounds for special recognition.

Legacy and Lessons

The story of Robert Hugo Dunlap offers enduring lessons about leadership, courage, and service that transcend the specific historical context of World War II. His life demonstrates that heroism often emerges from unexpected sources—that physical stature matters far less than strength of character, and that true leadership requires the willingness to share the risks faced by those under one's command.

Dunlap's decision to personally conduct reconnaissance under fire exemplifies a fundamental principle of military leadership: that officers must be willing to ask their subordinates to do nothing they would not do themselves. His two days of exposed fire direction, conducted while under constant enemy fire, showed how individual courage can multiply force effectiveness and save countless lives.

Perhaps most significantly, Dunlap's post-war life demonstrates that the same qualities that produce battlefield heroism—dedication, perseverance, and service to others—can be channeled into civilian pursuits that benefit entire communities. His eighteen years as a farmer and twenty years as an educator represent a different kind of service, no less valuable than his military contributions.

An Enduring Example

Today, as America continues to face global challenges that require both military excellence and civilian resilience, the example of Robert Hugo Dunlap remains remarkably relevant. His story reminds us that heroes often emerge from the most ordinary circumstances, that true courage manifests itself in service to others, and that the values that sustain democracy in wartime—courage, sacrifice, and dedication to duty—are equally essential in times of peace.

The quiet Marine from Abingdon who crawled forward under enemy fire to save his men, who spent two sleepless days directing artillery fire while exposed to constant danger, and who then returned home to serve his community as farmer and teacher, represents the best of American character. His Medal of Honor citation speaks of "conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity," but perhaps the most conspicuous aspect of Robert Hugo Dunlap's legacy is how seamlessly extraordinary courage blended with ordinary humility to create a life of exemplary service.

In an era when heroism is often confused with celebrity, the life of Major Robert Hugo Dunlap offers a different model—one in which true greatness emerges not from seeking attention, but from focusing on duty, service, and the welfare of others. This is the legacy that continues to inspire new generations of Americans, both in uniform and out, to pursue excellence in service to their country and communities.

Sources and Citations

- United States Marine Corps University, History Division. "Captain Robert Hugo Dunlap Medal of Honor Citation." Marine Corps University. https://www.usmcu.edu/Research/Marine-Corps-History-Division/People/Medal-of-Honor-Recipients-By-Unit/Capt-Robert-Hugo-Dunlap/

- Congressional Medal of Honor Society. "Robert H. Dunlap." Medal of Honor Recipients. https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/robert-h-dunlap

- National World War II Museum. "Captain Robert H. Dunlap's Medal of Honor." The National WWII Museum, February 15, 2022. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/captain-robert-dunlap-medal-of-honor

- U.S. Department of Defense. "Medal of Honor Monday: Marine Corps Maj. Robert H. Dunlap." Defense.gov, February 20, 2022. https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/Story/Article/2937033/medal-of-honor-monday-marine-corps-maj-robert-h-dunlap/

- Aerotech News & Review. "Medal of Honor Monday: Marine Corps Maj. Robert H. Dunlap." February 24, 2022. https://www.aerotechnews.com/blog/2022/02/28/medal-of-honor-monday-marine-corps-maj-robert-h-dunlap/

- SOFREP. "Remembering Robert H. Dunlap, USMC Feb 20-21, 1945, Iwo Jima, MOH." August 6, 2020. https://sofrep.com/specialoperations/remembering-robert-h-dunlap-usmc-feb-20-21-1945-iwo-jima-moh/

- Wikipedia Contributors. "Robert Hugo Dunlap." Wikipedia, October 10, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Hugo_Dunlap

- Military History Fandom. "Robert Hugo Dunlap." Military Wiki, February 23, 2024. https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Robert_Hugo_Dunlap

- WikiTree. "Robert Hugo Dunlap (1920-2000)." WikiTree FREE Family Tree. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Dunlap-1167

- Find a Grave. "MAJ Robert Hugo Dunlap (1920-2000)." Find a Grave Memorial. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7846147/robert_hugo-dunlap

- Veterans Memorial Park. "Welcome to the Abingdon Veterans Park." Abingdon Veterans Park. https://www.abingdonveteranspark.org/

- Simpson Ltd. "About Us." Firearms for Collectors, Galesburg, Illinois. https://www.simpsonltd.com/

- Military Trader. "Dealer Directory: Simpson Ltd." March 8, 2022. https://www.militarytrader.com/militaria-collecting-101/simpson-ltd

- Conservative Daily News. "Medal of Honor Monday: Marine Corps Maj. Robert H. Dunlap." February 21, 2022. https://www.conservativedailynews.com/2022/02/medal-of-honor-monday-marine-corps-maj-robert-h-dunlap/

- Fold3. "Robert Hugo Dunlap Memorial." Fold3 Military Records. https://www.fold3.com/memorial/638671005/robert-hugo-dunlap

- The Quiet Hero of Iwo Jima: Major Robert Hugo Dunlap's Extraordinary Legacy | Claude | Claude

Comments

Post a Comment